It was not until early adulthood that Leila paused to ask herself how and when her sexual awakening had occurred. By the time she had asked the question and had begun to feel than an answer was coming into focus, she had realized that it was quite futile to struggle to articulate the answer because the main person she wanted to present it to—her father—was not going to listen anyway. Still, although her musings on the topic of her own sexuality were destined to remain locked inside her own brain, she continued to cobble together a theory. The theory changed so often that it seemed to have a life of its own, and Leila felt almost helpless to pin it down.

It was certainly not a sudden sexual awakening; there was not a particular epiphany that prompted or preceded it. Nor was it a slow, gentle, or linear process. All she knew with certainty was that somewhere in between her past as a stubborn child with an equally stubborn cowlick and her present as a sophomore at Bryn Mawr, she felt the first stirrings of desire for female flesh. Sometime after those first stirrings, she began to accept the inevitability and inexorable push of them; she began to trace them to their roots, which were buried deep in the recesses of her psyche. Sometime after that, she began to suppress her confusion, and later her guilt about those feelings. Now, at age 23, she knew that she needed to accept her sexual orientation as a key component of her personality, and perhaps even begin to gradually construct a persona which used gay pride as a chief building material. But this was still proving a challenge.

Whenever her father came into the picture—when he was carnally present in her home, when she spoke to him on the phone, and even, at times, when she thought about him—the whole structure would begin to seem fragile and shaky. She knew she would never allow it to crumble altogether, because to do so would result in a devastating blow to her sense of herself. But it shook often, and this was a painful way to live.

When she first met Magda, she was so instantly smitten that she felt strong enough to take on not only her father, but all of Iran with its ridiculously antiquated dicta about homosexuality. In Iran, homosexuality was a crime punishable by death. Every square centimeter of Leila’s conscious mind was opposed to this attitude. But there were other parts of her mind that needed to respond too, and could not do so in such absolute terms. She wanted to believe that her more enlightened Iranian cousins would love her just the same if they knew the truth about her; that they would look past the minor detail about her sexual preference and remember that she was still Leila; that she was still their intelligent, strong-willed, morally upright cousin. She wanted to believe that they would remember her as the wild child to whose wisdom and creative genius they always deferred in their collective games under the trees of her grandfather’s bagh in the mountains of central Iran. Surely they could understand that the qualities they had seen in her then would still be alive in the 23-year-old lesbian version of cousin Leila.

In the crevices of her grown-up mind, though, she recognized that they would never be able to separate the essential Leila from the Leila they would now envision sharing a bed with a woman, even if that woman was the exotic, brilliant Magda. She was a woman whose intellect they would find formidable if they would ever pause to appreciate it; a woman whose life experience they would find rich and fascinating. If only they would allow themselves to know Magda. If only Magda weren’t a sexual deviant.

Magdalena Garrido Martin was everything Leila wanted in a companion. She was physically stunning, with an olive complexion and deep auburn hair that cascaded down her back. Her eyes were deep set and coffee-colored, and her frame was angular. She was not athletic, but she carried an energy in her body that made her seem physically powerful.

It seemed to Leila that Magda offset and complemented her own physique in a yin-yang sort of way. Leila was a compact, curvy woman who possessed a thin waist and wide hips she had inherited from her paternal grandmother. Magda told her that in certain positions, the shape of Leila’s hips made her look like a crouching cat, and jokingly referred to her hips as “haunches.” Leila wore her hair closely cropped, and the cowlick she had possessed as a child always emerged despite her best efforts to tame it. She had the heart-shaped face and arched eyebrows that were typical of the women in Persian miniatures, and her wire-rimmed glasses seemed to accentuate those features. Her face wore a permanently open expression that exuded kindness and honesty but also a certain no-nonsense firmness. She was masculine, but not butch. As a child, she had always felt like the name Leila was too feminine for her, and even considered for a time using her middle name, which was Elaheh. She noted with pride that she had more Iranian in her than American; more of her father than of her mother.

A fellow comparative literature major, Magda had been sent abroad by her well-to-do Spanish parents from her native Santander to study at Bryn Mawr. Leila met Magda at a lecture titled “Women Artists as Activists: The Failure of Assimilation,” being given by world-renowned anthropologist Dr. Roxanne Chabot as part of the Alice Paul Lecture Series. Leila and Magda chatted briefly at the champagne reception following the lecture. Leila, who was starry-eyed at the thought of being in the same room with Dr. Chabot, was impressed to see how blasé Magda was about her proximity to such a towering figure. During their brief conversation, each felt the other’s eyes scanning her face for a sign, and each radiated sexual availability and interest. Leila was normally quite shy, so she was proud of her own ease during the conversation with Magda. She even joked with her about her initials, “MGM,” and asked her if she was in any way connected to the media empire. Although no phone numbers were exchanged, a seed had been planted and each had gone away feeling confident there would soon be a follow-up.

Two days later, Madga appeared in the dining hall of Leila’s dorm and plopped her tray down at the table next to Leila’s. It was a mere coincidence that Leila just happened to be doing research for a paper she was writing on the picaresque tradition in literature, and was poring over dense passages of the Spanish classic Lazarillo de Tormes.

Magda met Leila’s eyes as she looked up from the book.

“I can help you with that if you want.” She lengthened her i in the word if so that it sounded more like eef. “I had to almost memorize it when I was in high school in Spain. Our high schools are more serious than yours, you know?”

Her accent made Leila’s heart skip a beat. “Okay. Let me test you,” she replied. “Who is speaking here?” She read a passage of the text aloud to Madga, taking care to pronounce the Spanish “c” and “z” with the proper Castilian lisp.

“Your Spanish is decent, but you have a Gringa accent,” Magda said, ignoring the challenge.

“I’m not sure what kind of accent you have, but it is beautiful,” stammered Leila.

“Let’s take a walk, and I’ll tell you all about Lazarillo. He is one of the greatest characters in all of Spanish literature. And of course, he is a quintessential Spaniard.”

Leila was amazed by the vastness of Madga’s English vocabulary. She did not know that the word quintessential was quite common in the Spanish lexicon, and actually traceable to the medieval Latin “Quinta Esencia” or “Fifth Element,” the coveted Philosopher’s Stone.

The relationship between Leila and Magda developed rapidly. The walk led to dinner at a Mediterranean café that very night, and ended in Madga’s single dorm room. From that point on, Magda and Leila were inseparable. It was a given that they would spend every night in one of the single dorm rooms they each had. In addition to this, they met each other between classes, went to plays, movies, concerts, and festivals together, took long bike rides together in the parks surrounding campus, and attended panel discussions and exhibitions together. Their weekends often involved “getaways” in Madga’s Honda Civic: they went to Pittsburgh and Chicago, to a cottage in the Poconos, and even, one long weekend, as far away as Niagara Falls, which Madga had been determined to see since she had first arrived in the United States. The relationship became so intense so quickly that it also became somewhat insular: both shut off their separate circles of friends, corresponded less frequently with their family members, and turned their attention exclusively toward one another.

Before meeting Magda, Leila had had only one other brief fling with a woman. It happened when she was at boarding school in England during her junior year. Leila’s father Dr. Khakbaz, recognizing a deep restlessness in his oldest daughter at her private international school in Tehran, had concluded that she was academically under-challenged and intellectually under-stimulated, and had made the decision to send her abroad to a boarding school in England. The decision was a heart-wrenching one for the doctor, as Leila had always been his favorite child. When she had fallen out of a tree at age five and had broken her arm, he had cut his hospital rounds short each day so he could go home early, even though he was just starting out in his practice and knew that this might jeopardize his reputation. A few years later, when Leila was twelve, she contracted scarlet fever. Once again, her father left his office early every afternoon throughout her convalescence, and stopped to buy her a gift each time. Thinking back on these gifts later, Leila sometimes wondered whether the doctor might have detected that her toy preferences suggested something more than tomboyishness: he had brought her a cap gun and cowboy hat, an erector set, and a slingshot.

Dr. Khakbaz had desperately missed his oldest daughter during her year away from home. He had flown her back to Tehran at Christmas and then again for spring vacation, and had even invited her close friend Liz, a pasty-faced British girl who had never been outside of the U.K., to spend the summer vacation in Iran. Had he known that Liz was the first woman his daughter had ever kissed, he would have sent her back to England forthwith—but in his ignorance of the true nature of their relationship, he took the two 16-year-olds on a tour of Isfahan, Shiraz, and Persepolis, blissfully unaware that these dazzling historic sites were fanning a the sparks of a romantic fire. At night in their hotel room, while he snored peacefully in the adjacent room, they cuddled and experimented with one another’s bodies.

At the end of the summer, after Liz returned to her own family in England, the doctor realized that he could not bear to part with Leila for another full year. In her absence something had begun to die within him; his life had somehow lost a dimension. Although he had already made the tuition payment for the fall term, he knew that he had to find a way to convince her to stay in Iran. He implored his wife Jane to apply gentle pressure on Leila, and he himself bribed her with a promise of an extended European tour the following summer, not only to visit her friends at boarding school but also to visit Paris and London and Rome. Leila eventually buckled. The relationship with Liz gradually fizzled out, although a few subtly suggestive letters were exchanged between the two girls for the first three or four months.

Jane and Aziz Khakbaz were completely unaware that during much of her adolescence, their oldest daughter filled the pages of several journals with bleak, cryptic, and highly imagistic poetry that she kept hidden in the locked drawer of her desk. They were even more unaware that their daughter was waking up to the realization that she preferred women to men.

* * * * *

But now, here was Magda, and there could no longer be any doubt in Leila’s mind about her sexual preference. Where Liz had been ethereal and simpering, Madga was solid and alive with color; where Liz had been a locked treasure chest, Madga was an open book, each chapter of which was richer and more complex than the one before. It wasn’t long after she took up with Magda that Leila realized that her life could no longer carry the same weight or meaning if she lost this woman. Everything inside her buzzed as though with an electric charge at the mere thought of Madga Garrido Martin.

Despite her determination to build her life around her relationship with Magda, Leila was always frightened that someone would spot the two of them on campus together and be horrified to learn the truth about her. Having grown up in Iran, where her well-known father had a huge network of acquaintances and maintained an immaculate reputation, Leila was accustomed to putting up outward shows of propriety. Madga, on the other hand, was absolutely brazen in her public displays of affection—even sexual desire—for Leila. She insisted on flaunting their relationship in an “in-your-face” manner. Although she was not a classic man-hating lesbian, she seemed to derive a special thrill from walking with her arm around Leila in places she knew were frequented by men of the “jock” persuasion: baseball games, parks that were full of male joggers; local pick-up bars. Times were changing, and there were some establishments in town that openly catered to gay patrons, but Madga seemed to enjoy mixed company almost more. She didn’t hate men, but she never missed the opportunity to define herself as their diametrical opposite.

Magda shared a number of anecdotes with Leila about her disastrous attempts to have relationships with men and her parents’ desperate attempts to find her a nice boyfriend from within Santander’s wealthy crowd. Leila was astonished to learn that Madga had “come out” to her parents several years earlier. Leila was familiar with the expression, but had never known anyone, male or female, who could claim to have made a clean breast about their homosexuality, least of all to their parents. Magda wore her sexual preference like a badge.

Leila, for her own part, shared the stories of her own miserable failures at joining the world of heterosexuals. She pretended to laugh along with Magda as she told these stories, but the truth was that they gave her such acute pangs of hurt and regret that she often lost sleep for days after remembering them. A particularly painful memory was of her pathetic one and only date to a school dance during her year in England with a freckled, acne-faced, buck-toothed boy named Colin. A group of Leila’s friends, perhaps sensing her latent sexual orientation, had spent hours helping her get ready for the dance, combing her hair to smooth out the cowlick, applying a gentle layer of foundation to cover up her adolescent spots and a light touch of lipstick to match the trim of her dress.

When they sat down at the dance, Leila’s dress had ridden up to reveal her thigh and Colin had reached over and put his hand on it, with his fingers dipping in between her legs. She had reacted immediately, reaching down and yanking his hand back into place on his own lap where it belonged. She had made a similar maneuver later on the dance floor when he began to move his hand up and down her back. When he tried to kiss her goodnight, she had felt physically ill by the closeness of his freckled face, and had jerked her head to the side so that she received the kiss on her cheekbone.

The idea of coming out was frightening enough to Leila—but the idea of coming out to her parents was simply unthinkable. Her mother’s abiding love would not waver, she knew, but she could not bear to consider the crushing hurt that the news would cause her. And coming out to the doctor was an idea that made Leila’s blood run cold. She knew that his bitter disappointment in his oldest daughter, his pride and joy, the child whose brilliance and success he hoped would enhance his reputation among Tehran’s doctor crowd, would be permanently devastating. The hurt would cut so deep that it would change Doctor Khakbaz forever.

She would never have the courage to “come out” to her parents.

Magda, of course, was not only shocked and dismayed by Leila’s cowardice, but bitterly disappointed to learn that her lover, the woman she had chosen as her “you-and-me-against-the-world” partner, was so un-whole, so uncertain of her own identity, so juvenile. When Leila tried to explain that Iranian culture judged homosexuality more harshly than it judged robbery, murder, or child abuse, Magda almost laughed out loud.

“Just because they do see it that way doesn’t make it right for them to see it that way. Come on, Leila! You have taken anthropology classes! You must understand that not everything in a culture is sacred, no matter how old or “traditional” it is! Also, a culture is not unchangeable, you know. Do you know how much Spain has changed already just in the two years since Franco died? Do you know that they didn’t even have toilets for women in lots of public places during the Franco regime because women weren’t supposed to go out of their houses?”

“Yes, Magda, but that’s Europe. We’re talking about Iran here. And we’re talking about Islam. Any time religion comes into the picture, the rules become really visceral and really convoluted.”

“Remember that we have religion in Spain, too. Did you ever hear of Catholicism? Don’t you know that Catholics also condemn homosexuality?”

* * * * *

When Magda proposed that Leila accompany her to Spain during summer vacation, Leila’s need to be honest with her parents came to a sudden head. They were expecting her to spend the summer in Iran, and the doctor had even secured a few weeks away from his private practice to accompany his family to the Caspian seacoast. Leila loved the Caspian, but she had been there many times. How could she reject a once-in-a-lifetime offer to visit the coast of Cantabria, which was reputed to be one of the most beautiful spots in the world? More importantly, how could she turn down the prospect of six weeks in one of the most gorgeous and romantic spots in the world in the company of the woman she loved?

She toyed with the idea of lying to her parents; of telling them that the trip to Spain was part of her program of study. This would have been believable: after all, she had taken several courses in Spanish literature, and had also been studying the Spanish language. But she told herself that lying to them was not only immoral, but cowardly. Sooner or later, she was going to have to “come out” and they were going to have to accept the inalterable truth of her sexual orientation. It might as well be now.

Leila knew that a phone call would be the most practical method for communicating this shattering news to her parents. But she could not bring herself to make the call. She knew that the moment she heard her father’s voice, full of love for her and anticipation of her upcoming visit, she would crumble. What she wanted to communicate would come out all wrong: she would couch the truth in deceptive rhetoric, and might end up not presenting the truth at all. Or, even worse, she would blurt it out in such harsh and absolute terms that she would end up in a long-distance shouting match with her father.

She had to tell them by email.

Once she had made the decision to write rather than calling, Leila endured several days of utter torment. She woke herself up in the middle of the night to compose sentences in her head, found her mind drifting during class, and became unusually distracted and clumsy. She could not muster full-hearted enjoyment even in Magda’s company. In fact, Magda was so decidedly unhelpful during this process that Leila barely wanted to see her at all. “Just write the damn email and stop thinking about it so much!” became Magda’s refrain—and not wanting to hear this refrain repeated so incessantly, Leila began avoiding her lover.

After several fits and starts and several lengthy drafts of dense and convoluted prose that she discarded, Leila finally decided that “concise and to-the-point” was best. She convinced herself that a quick, surgical move, like extracting a tooth, would be the easiest for her parents to handle: the pain would be acute but it wouldn’t last as long as it might if she wrote a rambling emotional piece that her parents would want to return to again and again.

She ended up with a single straightforward page:

My dear parents,

I will start this letter by asking you to take several deep breaths, as what you are about to read is going to hurt you. I would do anything in the world to avoid hurting you, but I have come to the realization that sooner or later, I must present to you a truth about myself that will inevitably hurt you no matter when I present it. I must ask you to try to pause and consider that the truth about me that I am about to reveal to you is not in my control, even though I know that this will not ease your pain.

I have met a woman here at Bryn Mawr, and she has changed my life. I will not deliver a long description of her or of our relationship in this letter. All I will say is that I love her more than I have ever loved anyone in my life, and that she has helped me to realize who I am.

This woman, whose name is Magda Garrido Martin, has asked me to spend the summer with her and her family in Santander, Spain. This is an opportunity I cannot turn down. I will not only have the privilege of visiting a beautiful country with a rich and fascinating history, but I will also have the opportunity to become acquainted with the family and culture of the woman I love.

I am relieved to have said this to you, even though I know that I have left you feeling bewildered and heartbroken. I will always love you with all my heart, and hope that you will continue to love me. Please call me when you receive this letter.

Your loving daughter,

Leila

Leila could not be certain that her parents would receive the email right away. Although the internet was available everywhere in Iran, and Iranians were among the most techno-literate people in the world, her parents often spent their weekends in their villa at the Caspian Sea, where they did not have a computer. During the agonizing wait that followed her email, Leila found that she needed Magda’s company more than ever. Being with Magda now was the only way she could keep sight of why she had written the letter that would change her parents’ lives. She found herself more mesmerized than ever by Magda’s dazzling wit, penetrating observations, and astounding erudition. Most of all, she found it comforting to turn to Magda in bed each night and to feel her strong, deep, protective embrace. Leila needed to feel that Magda could somehow replace the parents she had alienated—she needed to feel that Magda could be mother, father, and lover all rolled into one. She needed to feel the Magda was vital and vibrant enough to make up for a whole country, a whole culture, and a whole history she had willfully given up.

* * * * *

By the time Dr. Khakbaz made his phone call to Magda, he already had a plan in place, and had created a large network on the ground in the United States to help him execute this plan. The network included the following people: an Iranian psychiatrist who had been his colleague years ago at Georgetown and now had a private clinic in New York City; a brother-in-law who Leila had always liked and who now lived in New York City; a contact at the Admissions Office at Duke University; a travel agent. The psychiatrist would convince Leila that her condition was temporary and treatable; the brother-in-law would remind her of her Iranian heritage and would try to bring her back into the family fold; the admissions officer would process her paperwork so that she could transfer to another school; the travel agent had booked a hotel for the doctor near Bryn Mawr, had reserved two rooms at a hotel in New York City, and had two plane tickets ready for the doctor and Leila to fly from Philadelphia to New York City and from there back to Tehran.

The phone call itself was brief and business-like. The doctor knew what he wanted to say, and he spoke so rapidly and continuously that Leila was barely able to utter a word in response.

“Salaam, Leila-joon. It’s your Baba. I have read your letter, and I just wanted to let you know that I am flying to the United States on Tuesday so we can talk about this in person. I want to spend three days with you in Pennsylvania, and after that I want to take you to New York for the weekend. Is that okay with you?”

“I guess so,” was all that Leila managed to say.

Doctor Khakbaz’s arrived in Philadelphia as scheduled, and Leila met him at the airport. Instead of returning with her to campus, he took her out to dinner in the city and convinced her to stay the night in Philadelphia with him, where he had already reserved two hotel rooms.

During the dinner the doctor was soft and jovial, and the conversation was mostly light-hearted. Fearful of souring the mood, Leila did not bring up the issue at hand. Toward the end of the meal, over a glass of brandy, her father broached the subject himself. He had carefully planned not only the timing, but also the content, of what he was going to say.

His approach was to present homosexuality as a scientific phenomenon that resulted from a combination of genetic, hormonal, emotional, and environmental influences—a phenomenon was completely reversible. As he spoke, Dr. Khakbaz grew more animated but at the same time more affectionate, because he could sense that his method was working: he was leading Leila to the conclusion that she could become “normal” if only she would put herself into his capable hands. By the end of the evening, Leila’s head was spinning from the combination of the brandy and her father’s compelling discourse. It wasn’t so much the arguments themselves that were compelling; it was that her father had been gentle and loving. She fell into her hotel bed with a warm glow inside.

She was still feeling awash in her father’s love the next morning, and it was not difficult for him to convince her to drop out of Bryn Mawr effective immediately. The school was too small for a woman of her intellect and ambition, he explained, and the sooner she left, the better. Wouldn’t she like to travel with him to New York City this afternoon? They would stay for a few days with her favorite uncle, Amu-Abbas, and see all of the museums, Broadway plays, or lectures she wanted to see. While they were there she would have an appointment with a highly reputable psychiatrist who would talk over her problem with her. Then they would return to Iran for the remainder of the school year and the summer. In the fall, he promised to send her back to the United States where she would study at his alma mater, Duke University.

Leila’s love for Magda was strong, but the promise of deepening her bonds with her father and restoring his pride in her was stronger. Never one for histrionic displays of emotion, she did not cry or protest, but instead stifled her reactions and answered her father with dignity. She had a plan of her own: she would appease her father, then return to Magda in the fall and begin a secret life as a gay woman.

The culminating piece of Dr. Khakbaz’s master plan, the visit to New York City, was everything he had hoped it would be. He treated her like a princess, taking her to high-end restaurants and on shopping sprees, going with her to visit gallery exhibits he had no interest in and plays whose messages escaped him completely. Amu-Abbas was as brilliant and entertaining as ever. Although he was fully aware what was going on with Leila, Dr. Khakbaz had instructed him not to mention it, but instead to reminisce with Leila about her childhood in Iran and remind her of the rich cultural heritage she had abandoned.

Her father paid for her to make several long and tearful phone calls to Magda from her hotel in New York City, and even encouraged her to tell Magda that she would be returning in the fall and that they could be together again then.

It was not until she was leaving the office of the psychiatrist that Leila came to the realization that she had been manipulated. For the remainder of that school year and the long, hot summer that followed it, Leila languished in her childhood home in northern Tehran. Her parents made attempts to entertain her, introducing her to men and women her own age, hosting parties in her honor, taking her to the Caspian, buying her clothing and books and imported foods. State-of-the-art electronic devices were widely available in Iran, and Dr. Khakbaz came home one day with a brand new iPad wrapped up with a bow, even though it was not her birthday.

Beyond the windows of her bedroom, Leila spotted an occasional patch of blue sky peeking through the putrid cloud that hung in the air over the city. Whenever she did, or whenever she heard the chirping of birds or crickets above the din of Tehran traffic, she felt a momentary twinge of hope.

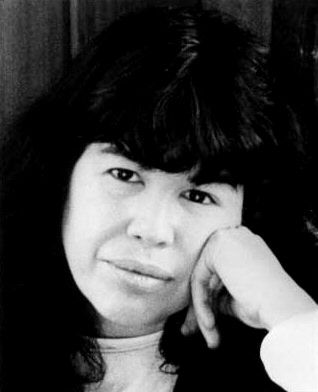

Susan Ehtesham-Zadeh is the product of a mixed-marriage between a high-profile Iranian doctor and a small-town American mother. She was born in Washington, D.C., came of age in Iran during the Shah’s era, received a degree in Philosophy from Stanford University, and returned to Iran shortly after Khomeini came to power. She later married a Spaniard from Madrid and spent significant chunks of her life in Europe. She is an English teacher and a freelance writer. She has authored two school histories as well as a number of personal essays, stories, and translations. Her work has appeared in the Quiddity International Literary and the Foundling Review. Several of her stories have been shortlisted by Able Muse and other journals.

Read More »

Tishani Doshi was born in the city formerly known as MADRAS in 1975.She has published five books of fiction, non-fiction and poetry. Her essays, poems and short stories have been widely anthologized. In 2012 she represented India at a historic gathering of world poets for Poetry Parnassus at the Southbank Centre, London. She is also the recipient of an Eric Gregory Award for Poetry, winner of the All-India Poetry Competition, and her first book, COUNTRIES OF THE BODY, won the prestigious Forward Prize for Best First Collection. Tishani’s debut novel, THE PLEASURE SEEKERS, was shortlisted for the Hindu Literary Prize and long-listed for the Orange Prize and the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. She currently lives on the beach between two fishing villages in Tamil Nadu with her husband and three dogs.

Tishani Doshi was born in the city formerly known as MADRAS in 1975.She has published five books of fiction, non-fiction and poetry. Her essays, poems and short stories have been widely anthologized. In 2012 she represented India at a historic gathering of world poets for Poetry Parnassus at the Southbank Centre, London. She is also the recipient of an Eric Gregory Award for Poetry, winner of the All-India Poetry Competition, and her first book, COUNTRIES OF THE BODY, won the prestigious Forward Prize for Best First Collection. Tishani’s debut novel, THE PLEASURE SEEKERS, was shortlisted for the Hindu Literary Prize and long-listed for the Orange Prize and the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. She currently lives on the beach between two fishing villages in Tamil Nadu with her husband and three dogs.

Michael Montlack is the author of the poetry book Cool Limbo (NYQ Books, 2011) and the editor of the Lambda Finalist essay anthology My Diva: 65 Gay Men on the Women Who Inspire Them (University of Wisconsin Press, 2009) as well as its “sister” poetry anthology Divining Divas (Lethe Press, 2012). He has been awarded residencies at (or scholarships from) the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, the Ucross Foundation, Lambda Literary Retreat, the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley and Tin House. Montlack splits his time between New York City, where he teaches at Berkeley College, and the West Coast.

Michael Montlack is the author of the poetry book Cool Limbo (NYQ Books, 2011) and the editor of the Lambda Finalist essay anthology My Diva: 65 Gay Men on the Women Who Inspire Them (University of Wisconsin Press, 2009) as well as its “sister” poetry anthology Divining Divas (Lethe Press, 2012). He has been awarded residencies at (or scholarships from) the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, the Ucross Foundation, Lambda Literary Retreat, the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley and Tin House. Montlack splits his time between New York City, where he teaches at Berkeley College, and the West Coast.

Nabila Lovelace is a born and raised Queens native, as well as a first generation American. Her parents hail from Trinidad and Tobago and Nigeria. She is a recent graduate of Emory University, and a winner of the 2013 Poets & Writers Amy Award. Currently she is living in Nanjing, China as a participant of the 2013-2014 AYC program. In her spare time she likes to eat Chocolate Chip cookies, and drink milkshakes.

Nabila Lovelace is a born and raised Queens native, as well as a first generation American. Her parents hail from Trinidad and Tobago and Nigeria. She is a recent graduate of Emory University, and a winner of the 2013 Poets & Writers Amy Award. Currently she is living in Nanjing, China as a participant of the 2013-2014 AYC program. In her spare time she likes to eat Chocolate Chip cookies, and drink milkshakes.