When she first saw him, Becky was heading into the 7-11 on Harper Avenue to buy a Slurpee, Twizzlers, and a pack of Camels. He was smoking. Vapor drifted from his lips as he leaned into the brick wall. His shoulders were relaxed, his head arched back. He wore a t-shirt with the Guns N’ Roses bullet ironed on the front, a pair of snug jeans, and black untied sneakers.

When Becky came out of the store – a plastic bag dangling from her wrist and a Slurpee in hand – he was in the same position; a crumpled cigarette lay on the ground beside him.

“Hey,” he said. He was a young, unwashed Bradley Cooper with narrow cheekbones, a pointy chin, and a scruffy beard that appeared red in the sunlight. He had piercing blue eyes that sank in his skin and he was older, maybe twenty-four. Becky typically went for college boys, but this wasn’t a college boy. This was a man.

“You come around here often?” he asked.

“What’s it to you?” Becky sucked on the thick red straw.

“I’m wondering why I haven’t noticed your beautiful face before.”

“I guess you weren’t paying attention.” Becky stepped closer to her car and away from this man, as she tucked the plastic bag into her fake leather purse.

“Well, I’m paying attention now, aren’t I?” he said.

She shrugged, a smile forming. He intimidated her and Becky rarely felt intimidated.

“Jay,” he said, as he extended his right hand. She hesitated, her fingers wrapped around the handle of her purse. She let go and took his hand.

“Becky,” she said.

“Fitting name.”

“Yeah?”

He nodded.

“You live around here?” she asked.

“I’m ten minutes that way,” he pointed. “How old are you?”

It felt abrupt, asking that, but Becky answered anyway, “Seventeen.”

“Well, you’re very beautiful.”

“You keep saying that,” she said. She’d heard those words before, but why did it sound so good coming out of his mouth? It must’ve been the way he smiled. As his lips curved, lines formed along his cheeks, and one small dimple creased in his left side.

“Just reiterating.”

“I have to go,” Becky said. She dug into the back pocket of her jeans to retrieve her keys.

“Will I see you again?” he asked, as he pulled out a phone from his pocket.

“Maybe.”

“Just maybe?”

“Yeah,” Becky said.

“Can I at least get your number?”

“If we meet again,” she said, figuring they wouldn’t. But what if they did?

“Deal.” He smiled. “It was very nice to meet you, Becky.”

Becky nodded, walking away. The chiming of her keys echoed in the warm summer air.

Three months passed before she saw him again. Becky and her friend, Julie, stopped at the 7-11 to pick up cigarettes and snacks. Becky instantly recognized the rugged-faced man that stood at the counter. Jay was buying a pack of Camels. He tucked his wallet back into his pants pocket, as Becky walked quickly past him.

“Becky,” he said, following behind.

She stopped and turned.

“Looks like we’re meeting again.”

“Jay,” she nodded. He looked good, better than she remembered. His brown hair had been clearly washed and combed; a wave formed at the left side of his head.

“I think we should go out,” he said matter-of-factly.

Becky looked down at the cigarettes in his hand, wondering if he knew those were her favorite. “Yeah? Why’s that?”

“Because fate’s brought us together again.”

She nodded, as she propped her hands on her narrow hips. Her body swayed ever-so-slightly.

“Have you been drinking?” he asked.

“No, of course not,” she lied.

Julie appeared beside them, hugging a liter of Coke, a bag of red plastic cups, and a large bag of Better Made potato chips.

“Becky, who’s this?” She asked. Becky wanted to lie and say that she didn’t know him, because she didn’t, not really.

“This is Jay,” she said.

Julie smiled, looking back and forth from Becky to Jay, and introduced herself.

They shook hands, as Becky slid her hands into her back pockets and looked towards candy section.

“How do you know each other?” Julie asked, as she bumped Becky’s arm with her shoulder.

Becky looked at Jay who was smiling. He scratched his beard with two fingers and laughed, as though their first meeting were a secret that only they shared, but it sort of was; Becky hadn’t mentioned him to anyone, least of all Julie. She didn’t think she’d needed to, or maybe she liked the idea of keeping the encounter solely to herself.

“Okay,” Julie said, breaking the silence. She turned away from Becky and fixed her eyes on Jay. “Well, we’re going to a party. You coming, Jay?”

What was she doing, Becky wondered.

“Okay,” he said. “What do you think?” he said to Becky.

It’s then that she noticed a small white scar on his caterpillar eyebrows. It stretched two inches further than the brown hairs. She wondered how he got it.

“You can come,” Becky agreed.

They went to a house in Roseville where Becky and Jay spent the next five hours drinking whiskey, smoking weed, and sitting on the brick patio overlooking a rundown backyard.

“Tell me your story,” Becky said, as she leaned down to pull chunks of grass out of the dirt.

“My story?”

“Come on,” she said.

Jay took a sip of his drink and leaned forward to rest his forearms on his legs.

“Too tragic, huh?” she said, as she dropped the bundle of fresh grass and sat upright.

His story poured out like syrup. He had dropped out of community college to take a job as a mechanic. He said he was raised in Detroit and his youngest brother died in a drive-by shooting. He said his parents were now divorced and living in separate cities, and he had season tickets to the Lions games and spent the majority of his free time visiting friends downtown.

“Why don’t you live in the city then?” Becky asked. “Apartments are pretty cheap, aren’t they?” She didn’t know; Becky only went to Detroit to buy booze. She bummed drugs off of friends, always too nervous to buy them herself.

“I like to get away, you know?”

“Yeah, I know.” Becky sipped on her warm whiskey-coke.

“Do you?” he said, surprised.

“My parents have a disastrous marriage. It wasn’t so bad with my sister around, but she moved to Kansas City with her boyfriend. He’s a fucking idiot, but she moved there after high school and now they have a three year old son.”

“You’re an aunt, huh?” Jay placed his empty hand on the brick just a few inches from Becky’s thigh.

“I’ve never even met him,” she said.

He nodded apathetically. “Shit happens.”

“Yeah, well,” she said, looking up at the vacant sky. “It’s all bullshit.” There wasn’t a star in sight.

“At least your parents don’t mind that you’re out, right?”

“They couldn’t care less,” she said, as she sipped on her drink.

“Well, I’m glad you’re here.” he said. He leaned in towards her.

Guys were peeing in the bushes ahead of them and strangers were smoking to their right, but Becky could only focus on Jay and his lips. She didn’t even mind that his beard scratched her chin or that his forehead was sweaty.

An hour later, after Julie left, Becky went back to Jay’s apartment which strongly resembled a college guy’s dorm room. There was junk piled up in corners, walls lacking decor, a massive flat screen TV, and a kitchen filled with dirty dishes. Aside from two small containers of peanuts and a heavy supply of liquor on the counter, there was nothing else in the kitchen area. It seemed as though he were squatting and not living there.

“Don’t you cook?” Becky asked, as she slid her hand across the smooth kitchen countertop. Jay laughed, as he poured them both a drink.

“Do grilled cheese sandwiches count?”

Becky laughed. “No.”

“Then no; not really.”

He handed her a heavy dose of bourbon in a plastic green tumbler.

“Cheers,” he said. They bumped glasses. Then Jay led Becky over to the black leather couch. It was either used or really old, or both. It was covered in grey scuffs with two small slashes and imprints of various body shapes were embedded in the fabric.

It suddenly occurred to Becky that Jay lived alone. He didn’t have roommates or parents. Nobody would come out of their rooms or through the front door and nobody would hear if they had sex or if she screamed.

Becky cradled the cold glass in her hands.

“So this whole Ferguson thing,” she said casually, as though she were mentioning simple weather changes. It was the only headline she could recall reading in the news that week.

“Fucking cops,” he said. He shook his head.

“Yeah, the whole thing’s strange,” Becky agreed, though she wasn’t quite sure what to believe. She only knew the basics of the murder, but hadn’t read the details.

“No, it’s a fucking mess. Cops are assholes,” he said more adamantly.

His assertion was sinister, yet sexy.

“Why are we talking about this?” he asked, as he placed his hand on Becky’s thigh.

“I don’t know,” she said. His hand was warmed her bare skin. “What do you want to talk about?”

“Nothing.” He said. She turned to him and next thing she knew, her glass was on the table and they were kissing. It all happened rather quickly. His legs were pressed against hers and then his fingers traced the bones in her spine, as he moved up Becky’s back towards her bra strap. Then Jay aimed for her sensitive spot; the neck. His calloused fingers slid up through her hair and fixed on the lower part of her head, pulling her closer to him. His movements were strategic and tantalizing. It was obvious Jay knew what to do with a woman; he knew how to make her feel sexy, and most importantly, desirable. Becky’s arousal continued to build, leaving Jay in full control of her body.

It escalated and before she knew it, Becky was naked on the floor, propped on her hands and knees, as Jay pushed from behind. While he was thrusting, his hands crept up and down her body and then planted firmly on her hips. He held her tightly, his fingers laced around her bones, and when he came, he removed one hand to tug her long brown hair.

Within a few weeks, Becky was spending three to four nights per week at Jay’s place. She told her parents she was staying at Julie’s apartment and they had no reason not to believe her. She had never been particularly close to her parents; her father was easily angered, her mother overly emotional, and they both took quite strongly to alcohol. Becky, herself, had started drinking when she was fifteen. That same year, she met Julie and they clicked instantly. Now that she was spending more and more time with Jay, she saw less and less of Julie.

She quickly grew accustomed to Jay’s weird work hours, his insomnia, his greasy grilled cheese sandwiches, and his lack of simple household items like conditioner and dish soap. He knew exactly how to treat a lady, a feeling Becky had never know. He paid attention to her, always asking follow-up questions, and he’d kiss her forehead, just because. He’d rub her back when it was sore and he’d walk down to the corner store to buy her coffee, breakfast, or a pack of cigarettes.

While they were sitting, half-naked, on the couch one morning, Becky asked if she could buy a coffee maker for his apartment.

“It’d be cheaper than buying it all the time,” she said.

“Anything you want, baby.”

“Anything, huh?’

“So long as I’m not buying it,” he said, his attention focused on the TV.

“There is another thing I want and it doesn’t cost anything.”

“What’s that?”

Becky pulled at a strand of her hair, twisting it around her forefinger.

“Well, we’ve been dating for a while now.” Three months seemed like a while. It was certainly the longest relationship Becky had ever had.

“That’s true.”

“How about making it official?” She felt like a middle school girl asking some boy to dance with her. It was silly, she decided. Surely Jay would think it was silly. Becky shouldn’t have said anything.

Jay leaned forward, focusing on the Tigers game, and said, “Of course.”

“Really?”

“You know you’re my girl.”

Becky blushed. Jay would be her first official boyfriend. She had had hookups, and dates before, but not boyfriends. Relationships never seemed to work for her. Either the guy was unwilling to commit or she wasn’t into it, but this felt different. Jay was different.

Becky was in her room, when she heard a commotion. Her parents had been arguing for a while, but that wasn’t unusual. She lowered the music. Weirdly enough, it was quiet, and that scared Becky more than the fighting. She turned off the music completely and listened. Nothing.

Becky went to the kitchen and found her mother sitting at the table with her head in her hands, her body shaking. Becky glanced around. A glass bottle had shattered; pieces were scattered across the counter and the floor. There was a small trail of blood on the wood, presumably her mother’s.

“Mom,” she said. “Holy fuck. Mom, what the hell happened.” Now Becky was shaking.

Her mother looked up. Blood poured from her cheek.

“Holy shit. Mom, oh my god.”

Becky went straight for the towel hanging off the oven handle, careful to avoid the glass. She pressed the striped towel to her mother’s face, then took off her sweater and wrapped it around her mother’s arm. The blood slowly soaked the fabric and dribbled down Becky’s hand.

“We need to take you to the ER. What the fuck happened?”

“It was my fault,” her mother said. She wouldn’t look at Becky.

“It’s not your fault, Mom. This is a fucking mess. I’m calling 9-11.”

“No, Becky, I’m fine.”

“Hold this,” Becky demanded. Her mother took the towel with her right hand and held it against her cheek.

Becky ran to get her cell phone and called the cops. They arrived eight minutes later and took Becky’s mother away on a stretcher. She was stitched up and tested for internal head injuries.

Two hours later, Becky was sitting in the chair beside her mother’s hospital bed.

“Mom, you have to tell me what happened. Where’s Dad?”

“He left.”

“What do you mean, he left?”

“He’s gone, Becky,” she said.

“Mom, seriously, tell me what happened.” Becky needed to understand. Her father had never hurt her mother before, at least not physically. Verbally, yes, but never physically.

“He threw a bottle of wine,” she said.

“At you?” Anger trickled through Becky’s body.

“No, at the wall. It shattered.”

“God damnit, mom.”

“He left me, Beck,” she said. “Isn’t that enough?” Her mothers’ eyes filled with tears.

Becky’s parents had met in high school and married when they were both twenty years old. Five months later, they had Becky’s older sister, and two years later, they had Becky. For as long as she could remember, Becky’s parents had fought over money, schedules, jobs, parenting. Their relationship was toxic.

Sitting in that sterile room, staring at her mother’s bandaged face, Becky couldn’t help feeling sorry for her. She reached around the IV and linked her fingers around her mother’s wrinkly hand, wondering when she had last touched her mother; not since she was young and had to hold her mother’s hand when crossing the street.

A few weeks after the incident, Becky returned home from Jay’s, and found her mother sitting in the corner of the living room with her back to the wall and her knees pressed to her chest. A pile of papers sat beside her.

“Mom, what are you doing?”

“He wants a divorce.”

Becky expected this, but instead of feeling relief, she felt a strange pang of heartache. She joined her mother on the floor in an attempt to comfort her. When Becky’s mother lifted her head, she said, flatly, “I don’t have enough money.”

“It’ll be fine,” Becky promised. It’s exactly what her parents had always told her; not that she ever believed them.

Her mother stood, leaving the papers behind, and said, “You need to get a job, Becky. I don’t care what it is, but you need to do something.” Her mother leaned against the couch, closed her eyes, and dropped her head in shame. “I can’t pay for your shit anymore,” she said. Then she opened her eyes, dropped her arms, and drifted down the hallway.

“I have a friend who could help,” Jay offered.

“Really? What does he do?”

“He’s got a good business, and you’d do well.”

“What would I do?”

“It’s a dating service,” he said matter-of-factly.

“A dating service? What the fuck does that mean?”

“All you have to do is escort rich men to events. It’s easy and it pays. You’ll make over $400 a night; easy”

Becky felt uneasy. “I don’t think so.”

“Why not?”

“Is it safe?”

“Of course it’s safe. Forget I mentioned it. If you don’t want my suggestions, don’t ask,” he replied bitterly.

“I’m sorry,” Becky said. She let go of the spoon in her hand and touched Jay’s arm. They were both sitting in front of the TV, holding a bowl of cereal.

“Thanks, I’ll think about it, okay?” Becky said.

“You said you needed the money.”

She returned to her fruit loops and waited until the next commercial to ask, “Wouldn’t it bother you?”

“What?”

“The escort thing?”

“Why would it bother me?” he asked, serious.

“Because, I’d be going out with other men. Isn’t that kind of weird?” It was, Becky decided.

“You’d be good at, and you need the money, don’t you?”

“Yeah, I guess.” Becky took another bite of her cereal, thinking maybe he was right; she needed money.

Two weeks later, Becky found herself in the backseat of a Honda with a strange man. His name was Robert, he was a businessman, and he needed a date for a client meeting. He had requested a tall brunette with long legs and a decent ass. The night before, Jay took Becky to JC Penny’s to pick out a new dress, ultimately deciding on a short cobalt blue dress that formed a V in the back, forcing her to go braless. She felt naked and exposed in the thin fabric, but Jay had recommended it for those very reasons.

Robert’s personal driver had picked Becky up from Jay’s and now they were headed to his client meeting.

“How old are you?” Robert asked, as he brushed his hand through his sleek black hair.

“Seventeen,” Becky said.

“Twenty.”

“I’m seventeen,” she repeated.

“With me, you’re twenty,” Robert said.

“I don’t look twenty,” she said.

He ignored her. “Know anything about stocks?”

“No.”

“Great. Just smile and look pretty. If anybody asks, tell them you’re a hairdresser. You can do that, right Becky?”

“Sure.” She turned towards the window and watched as cars swished past.

It was a long night, over three hours. They sat in a private back room of a crowded restaurant, and shared a four course meal. Becky remained quiet as she ate. When somebody asked how much money she made hairdressing, she said, “fifteen an hour.” They nodded in approval and asked what she thought of Obama. Becky had said, “He’s great” and the men all laughed, before returning to work. Becky had never felt as young and inferior as she did that night, as though she were just a fixture on the wall and nothing more.

Towards the end of the dinner, right before dessert, Robert leaned over and said, “Why you don’t you give us a few minutes. Go fix yourself or something and come back in fifteen minutes.”

Becky smiled politely and excused herself from the table. She was glad to leave that room, but as she stood in the bathroom, staring at herself in the mirror, she felt nauseous. She had worn too much makeup, but Jay had encouraged it, and she was showing too much side-boob.

It disturbed her, being in a strange restaurant with a strange man, not having any say in where she went or what she did. But she obeyed, because Jay promised it was safe, and he was right, she needed the money. Did it matter where the money came from? Becky wondered, knowing the answer.

After dinner, Robert showed Becky back to the car. When they were both settled into the back seat, he pulled out a cigarette and lighter.

“Can I have one?” Becky asked.

He lit it, handed it over, and then reached for another. They rolled down their windows and breathed in the tobacco. Becky felt a sudden high. Smoking was a comfort, an addiction, and she felt at ease despite the circumstances.

“You did well,” Robert said, as he brushed his cold hand across her bare knee. Becky sat upright, suddenly alert.

“Thanks,” she said as she lifted the cigarette to the window.

“Maybe we can do this again,” he said, as he grew increasingly, uncomfortably close to Becky. She anticipated a kiss or a boob grab, as if she were on a bad date, so she scooted closer to the warm air. Instead, Robert reached into the inside pocket of his suit coat and handed over a folded stack of clean bills. Becky took the wad, pressed it into her purse, and politely thanked him.

That night, Jay insisted on counting the cash for her. He took it, walking towards his bedroom, and returned with a smile, revealing that dimple.

“He must’ve liked you, huh?”

Becky shrugged, “I guess; I didn’t do much.”

“You didn’t have to.” Jay approached Becky and latched onto her hips. “Come here, sexy.” He pulled her towards him, his breath on her cheek.

“I don’t know if I’ll do that again.” She said, as Jay kissed her cheekbone, the back of her jaw, and then her earlobe. His muscular body was wrapped tightly around her thin frame.

“It was easy, wasn’t it?” he said with a growly voice.

“Yeah, but I didn’t like it.”

He pulled back, his hands still on her waist. “What’s not to like?” He looked down on her. “You keep this up, and you’ll be making bank. It’s good business, you’ll see.”

“Is it?”

“Cash is cash, Beck, and you need it, don’t you,” he said.

She remained quiet, as the words rushed over her like the steam in a hot shower.

You need it, don’t you.

Jay resumed the kissing, and Becky discarded the words, hoping they’d disappear from her memory, but she already knew they’d resurface like a dead fish.

On her third date with Robert, she was taken to a dive bar in downtown Detroit. He held her hand, leading her through the dimly-lit room, until he found his people in the far corner. There were three guys; all dressed in suits, their coats open revealing button-up shirts and stray chest hairs. Each held a glass of brown liquor and Becky quickly learned that these guys were friends, not co-workers.

Sitting there, all done up, Becky felt like a cufflink, clinging to Robert’s arm as though her sole purpose was to look expensive. Robert and his pals urged Becky to drink so she did and the longer they stayed, the drunker she got. They indulged her; offering shots and drinks over and over again.

Becky stumbled to the bathroom, feeling as though she were being pushed from both sides. She bent down to vomit in the toilet and only when she felt capable of standing did she return. It could have been minutes or hours, Becky wasn’t sure, but the men didn’t seem to notice her absence. Robert and a friend linked arms with Becky and led her back to the car. Everything was spinning; the cars in the parking lot, the stars in the sky. Their laughter echoed, burning her ears.

Once in the backseat, Becky became hypersensitive, feeling the bass of the music in her forehead. Halfway home, Robert put his hand on Becky’s leg. He dragged it all the way up to her lacy underwear. Becky was too drunk to react, but she knew it was all wrong.

“Not okay,” she slurred.

“It’s alright, baby, it won’t hurt.”

Suddenly his hand was pressed to her mouth, shutting her up, as he yanked her underwear down, and shoved his fingers inside. It hurt, that much she knew, but she couldn’t stop him. She could hardly comprehend the events, her mind racing, and the world spinning. He continued, and then, just as quickly, he was inside her. Certain her screams, though muffled, were audible, Becky looked to the driver, his eyes fixated on the road. She struggled to push him away, but she was weak and he persisted, coming inside of her.

When the car finally stopped, Robert had buttoned up his pants and now he handed her a pile of cash. She took it, unable to comprehend what just happened. She looked again at the driver, but he was looking away as she stepped out of the car in her tiny dress.

She stood outside Jay’s door and cried.

“Beck, what’s the matter?” he said, letting her inside.

“He,” she started, but the words wouldn’t come.

“Are you hungry?” Jay asked, changing subjects.

“No,” she gasped.

“Why don’t we go sit down.”

Becky collapsed on the couch, the cold leather grazing her skin. Only then did she realize her underwear was left on the floor of the car. The tears fell faster.

“Stop crying, Beck, and tell me what’s wrong.”

After she finally said, “He raped me.”

“Oh, Becky,” he said, as he held her and rubbed the back of her head. She cried into his shoulders, the scotch attempting to crawl back up her throat.

She felt dirty and nauseous, but eventually the tears stopped and she drifted to a light sleep.

She awoke on the couch, alone, in last night’s dress, with a flannel blanket wrapped around her body. She stretched out her limbs, suddenly aware of her sore thighs. In an instant, Becky felt the weight of the previous night crushing her delicate body. She sat upright, her stomach lurching forward in an attempt to vomit, but nothing came out.

“Hey you,” Jay said casually from the open kitchen. He was dressed in a pair of sweats holding two mugs.

“I have coffee,” he said with a smile, as though it were a typical morning.

He sat on the far end of the couch and handed over the blue and green striped mug. Becky took it, and then yanked at Jay’s arm, begging him to be closer.

“We need to tell somebody,” she said with a quiet concern.

“We can’t, Beck,” he said matter-of-factly.

“He can’t do that.”

“Sure he can. He paid you.” Jay said then took a sip of coffee.

In sync with her pounding headache, Becky’s heart raced. Did that make her a prostitute? No, she didn’t sign up for that. She was an escort, nothing more.

Becky put the mug on the table and fell into Jay’s chest. With his free hand, he rubbed her shoulder and then kissed the top of her greasy hair.

Jay turned on the TV and only after three episodes of Friends did Jay say, “You might not want to hear this, but you made a killing last night.”

“What?” Becky lifted her head from his chest.

“Yeah, eleven hundred.”

“Seriously?” In an attempt to forget about the night, she’d also forgotten about the money.

“I know he shouldn’t have done that,” Jay said, “but it wasn’t so bad, was it?”

Becky pushed herself up so she was hovering over Jay. “What are you talking about?”

“I’m just saying; it’s not that big of a deal.”

“It is a big deal,” she returned, the anger building.

“Listen, Beck, I really like you. Hell, I love you, but this is something you have to do. Don’t worry about me, okay? I support you.”

“Are you kidding? I don’t want to do that ever again.”

“Beck, you need the money, and honestly, I can’t keep paying for your shit. It’s a good thing you got this gig. You can start contributing and you can get different clients, if you want; that’s not a big deal.”

“Are you serious?” Becky stood off the couch. Everything felt wrong.

“Beck, don’t get like that, okay?”

“You just said you love me. Now you want me to prostitute myself?” She couldn’t believe she’d even said it aloud.

“It’s not like that,” he said, as he stood and grabbed her hand. “You have to support yourself and your mom. I’ll be here, alright, no matter what. I’m yours, remember?”

Thousands of emotions rushed through Becky’s body like the blue dye from an MRI. She felt warm and jittery.

“But it hurt,” she admitted, as Jay let go of her sweaty hand.

“It won’t, after a while.” He wrapped his body around her, smothering her with the smell of cigarettes and coffee. “Just make sure they wear condoms,” he said. “I don’t want any guy knocking up my girl,” he snickered.

Becky looked up at Jay. His round eyes were fixed on her. He was smiling lovingly, holding her tightly, and promising her welfare. Maybe he was right; maybe it was for the best. She did need the money and Becky trusted Jay. If he was okay with it, then why wasn’t she?

“You’ll still love me?” she pleaded.

“Of course,” he promised. “It’ll be worth it, you’ll see.”

Becky closed her eyes as Jay kissed her oily forehead.

When she first saw him, Becky was heading into the 7-11 on Harper Avenue to buy a Slurpee, Twizzlers, and a pack of Camels. He was smoking. Vapor drifted from his lips as he leaned into the brick wall. His shoulders were relaxed, his head arched back. He wore a t-shirt with the Guns N’ Roses bullet ironed on the front, a pair of snug jeans, and black untied sneakers.

When Becky came out of the store – a plastic bag dangling from her wrist and a Slurpee in hand – he was in the same position; a crumpled cigarette lay on the ground beside him.

“Hey,” he said. He was a young, unwashed Bradley Cooper with narrow cheekbones, a pointy chin, and a scruffy beard that appeared red in the sunlight. He had piercing blue eyes that sank in his skin and he was older, maybe twenty-four. Becky typically went for college boys, but this wasn’t a college boy. This was a man.

“You come around here often?” he asked.

“What’s it to you?” Becky sucked on the thick red straw.

“I’m wondering why I haven’t noticed your beautiful face before.”

“I guess you weren’t paying attention.” Becky stepped closer to her car and away from this man, as she tucked the plastic bag into her fake leather purse.

“Well, I’m paying attention now, aren’t I?” he said.

She shrugged, a smile forming. He intimidated her and Becky rarely felt intimidated.

“Jay,” he said, as he extended his right hand. She hesitated, her fingers wrapped around the handle of her purse. She let go and took his hand.

“Becky,” she said.

“Fitting name.”

“Yeah?”

He nodded.

“You live around here?” she asked.

“I’m ten minutes that way,” he pointed. “How old are you?”

It felt abrupt, asking that, but Becky answered anyway, “Seventeen.”

“Well, you’re very beautiful.”

“You keep saying that,” she said. She’d heard those words before, but why did it sound so good coming out of his mouth? It must’ve been the way he smiled. As his lips curved, lines formed along his cheeks, and one small dimple creased in his left side.

“Just reiterating.”

“I have to go,” Becky said. She dug into the back pocket of her jeans to retrieve her keys.

“Will I see you again?” he asked, as he pulled out a phone from his pocket.

“Maybe.”

“Just maybe?”

“Yeah,” Becky said.

“Can I at least get your number?”

“If we meet again,” she said, figuring they wouldn’t. But what if they did?

“Deal.” He smiled. “It was very nice to meet you, Becky.”

Becky nodded, walking away. The chiming of her keys echoed in the warm summer air.

Three months passed before she saw him again. Becky and her friend, Julie, stopped at the 7-11 to pick up cigarettes and snacks. Becky instantly recognized the rugged-faced man that stood at the counter. Jay was buying a pack of Camels. He tucked his wallet back into his pants pocket, as Becky walked quickly past him.

“Becky,” he said, following behind.

She stopped and turned.

“Looks like we’re meeting again.”

“Jay,” she nodded. He looked good, better than she remembered. His brown hair had been clearly washed and combed; a wave formed at the left side of his head.

“I think we should go out,” he said matter-of-factly.

Becky looked down at the cigarettes in his hand, wondering if he knew those were her favorite. “Yeah? Why’s that?”

“Because fate’s brought us together again.”

She nodded, as she propped her hands on her narrow hips. Her body swayed ever-so-slightly.

“Have you been drinking?” he asked.

“No, of course not,” she lied.

Julie appeared beside them, hugging a liter of Coke, a bag of red plastic cups, and a large bag of Better Made potato chips.

“Becky, who’s this?” She asked. Becky wanted to lie and say that she didn’t know him, because she didn’t, not really.

“This is Jay,” she said.

Julie smiled, looking back and forth from Becky to Jay, and introduced herself.

They shook hands, as Becky slid her hands into her back pockets and looked towards candy section.

“How do you know each other?” Julie asked, as she bumped Becky’s arm with her shoulder.

Becky looked at Jay who was smiling. He scratched his beard with two fingers and laughed, as though their first meeting were a secret that only they shared, but it sort of was; Becky hadn’t mentioned him to anyone, least of all Julie. She didn’t think she’d needed to, or maybe she liked the idea of keeping the encounter solely to herself.

“Okay,” Julie said, breaking the silence. She turned away from Becky and fixed her eyes on Jay. “Well, we’re going to a party. You coming, Jay?”

What was she doing, Becky wondered.

“Okay,” he said. “What do you think?” he said to Becky.

It’s then that she noticed a small white scar on his caterpillar eyebrows. It stretched two inches further than the brown hairs. She wondered how he got it.

“You can come,” Becky agreed.

They went to a house in Roseville where Becky and Jay spent the next five hours drinking whiskey, smoking weed, and sitting on the brick patio overlooking a rundown backyard.

“Tell me your story,” Becky said, as she leaned down to pull chunks of grass out of the dirt.

“My story?”

“Come on,” she said.

Jay took a sip of his drink and leaned forward to rest his forearms on his legs.

“Too tragic, huh?” she said, as she dropped the bundle of fresh grass and sat upright.

His story poured out like syrup. He had dropped out of community college to take a job as a mechanic. He said he was raised in Detroit and his youngest brother died in a drive-by shooting. He said his parents were now divorced and living in separate cities, and he had season tickets to the Lions games and spent the majority of his free time visiting friends downtown.

“Why don’t you live in the city then?” Becky asked. “Apartments are pretty cheap, aren’t they?” She didn’t know; Becky only went to Detroit to buy booze. She bummed drugs off of friends, always too nervous to buy them herself.

“I like to get away, you know?”

“Yeah, I know.” Becky sipped on her warm whiskey-coke.

“Do you?” he said, surprised.

“My parents have a disastrous marriage. It wasn’t so bad with my sister around, but she moved to Kansas City with her boyfriend. He’s a fucking idiot, but she moved there after high school and now they have a three year old son.”

“You’re an aunt, huh?” Jay placed his empty hand on the brick just a few inches from Becky’s thigh.

“I’ve never even met him,” she said.

He nodded apathetically. “Shit happens.”

“Yeah, well,” she said, looking up at the vacant sky. “It’s all bullshit.” There wasn’t a star in sight.

“At least your parents don’t mind that you’re out, right?”

“They couldn’t care less,” she said, as she sipped on her drink.

“Well, I’m glad you’re here.” he said. He leaned in towards her.

Guys were peeing in the bushes ahead of them and strangers were smoking to their right, but Becky could only focus on Jay and his lips. She didn’t even mind that his beard scratched her chin or that his forehead was sweaty.

An hour later, after Julie left, Becky went back to Jay’s apartment which strongly resembled a college guy’s dorm room. There was junk piled up in corners, walls lacking decor, a massive flat screen TV, and a kitchen filled with dirty dishes. Aside from two small containers of peanuts and a heavy supply of liquor on the counter, there was nothing else in the kitchen area. It seemed as though he were squatting and not living there.

“Don’t you cook?” Becky asked, as she slid her hand across the smooth kitchen countertop. Jay laughed, as he poured them both a drink.

“Do grilled cheese sandwiches count?”

Becky laughed. “No.”

“Then no; not really.”

He handed her a heavy dose of bourbon in a plastic green tumbler.

“Cheers,” he said. They bumped glasses. Then Jay led Becky over to the black leather couch. It was either used or really old, or both. It was covered in grey scuffs with two small slashes and imprints of various body shapes were embedded in the fabric.

It suddenly occurred to Becky that Jay lived alone. He didn’t have roommates or parents. Nobody would come out of their rooms or through the front door and nobody would hear if they had sex or if she screamed.

Becky cradled the cold glass in her hands.

“So this whole Ferguson thing,” she said casually, as though she were mentioning simple weather changes. It was the only headline she could recall reading in the news that week.

“Fucking cops,” he said. He shook his head.

“Yeah, the whole thing’s strange,” Becky agreed, though she wasn’t quite sure what to believe. She only knew the basics of the murder, but hadn’t read the details.

“No, it’s a fucking mess. Cops are assholes,” he said more adamantly.

His assertion was sinister, yet sexy.

“Why are we talking about this?” he asked, as he placed his hand on Becky’s thigh.

“I don’t know,” she said. His hand was warmed her bare skin. “What do you want to talk about?”

“Nothing.” He said. She turned to him and next thing she knew, her glass was on the table and they were kissing. It all happened rather quickly. His legs were pressed against hers and then his fingers traced the bones in her spine, as he moved up Becky’s back towards her bra strap. Then Jay aimed for her sensitive spot; the neck. His calloused fingers slid up through her hair and fixed on the lower part of her head, pulling her closer to him. His movements were strategic and tantalizing. It was obvious Jay knew what to do with a woman; he knew how to make her feel sexy, and most importantly, desirable. Becky’s arousal continued to build, leaving Jay in full control of her body.

It escalated and before she knew it, Becky was naked on the floor, propped on her hands and knees, as Jay pushed from behind. While he was thrusting, his hands crept up and down her body and then planted firmly on her hips. He held her tightly, his fingers laced around her bones, and when he came, he removed one hand to tug her long brown hair.

Within a few weeks, Becky was spending three to four nights per week at Jay’s place. She told her parents she was staying at Julie’s apartment and they had no reason not to believe her. She had never been particularly close to her parents; her father was easily angered, her mother overly emotional, and they both took quite strongly to alcohol. Becky, herself, had started drinking when she was fifteen. That same year, she met Julie and they clicked instantly. Now that she was spending more and more time with Jay, she saw less and less of Julie.

She quickly grew accustomed to Jay’s weird work hours, his insomnia, his greasy grilled cheese sandwiches, and his lack of simple household items like conditioner and dish soap. He knew exactly how to treat a lady, a feeling Becky had never know. He paid attention to her, always asking follow-up questions, and he’d kiss her forehead, just because. He’d rub her back when it was sore and he’d walk down to the corner store to buy her coffee, breakfast, or a pack of cigarettes.

While they were sitting, half-naked, on the couch one morning, Becky asked if she could buy a coffee maker for his apartment.

“It’d be cheaper than buying it all the time,” she said.

“Anything you want, baby.”

“Anything, huh?’

“So long as I’m not buying it,” he said, his attention focused on the TV.

“There is another thing I want and it doesn’t cost anything.”

“What’s that?”

Becky pulled at a strand of her hair, twisting it around her forefinger.

“Well, we’ve been dating for a while now.” Three months seemed like a while. It was certainly the longest relationship Becky had ever had.

“That’s true.”

“How about making it official?” She felt like a middle school girl asking some boy to dance with her. It was silly, she decided. Surely Jay would think it was silly. Becky shouldn’t have said anything.

Jay leaned forward, focusing on the Tigers game, and said, “Of course.”

“Really?”

“You know you’re my girl.”

Becky blushed. Jay would be her first official boyfriend. She had had hookups, and dates before, but not boyfriends. Relationships never seemed to work for her. Either the guy was unwilling to commit or she wasn’t into it, but this felt different. Jay was different.

Becky was in her room, when she heard a commotion. Her parents had been arguing for a while, but that wasn’t unusual. She lowered the music. Weirdly enough, it was quiet, and that scared Becky more than the fighting. She turned off the music completely and listened. Nothing.

Becky went to the kitchen and found her mother sitting at the table with her head in her hands, her body shaking. Becky glanced around. A glass bottle had shattered; pieces were scattered across the counter and the floor. There was a small trail of blood on the wood, presumably her mother’s.

“Mom,” she said. “Holy fuck. Mom, what the hell happened.” Now Becky was shaking.

Her mother looked up. Blood poured from her cheek.

“Holy shit. Mom, oh my god.”

Becky went straight for the towel hanging off the oven handle, careful to avoid the glass. She pressed the striped towel to her mother’s face, then took off her sweater and wrapped it around her mother’s arm. The blood slowly soaked the fabric and dribbled down Becky’s hand.

“We need to take you to the ER. What the fuck happened?”

“It was my fault,” her mother said. She wouldn’t look at Becky.

“It’s not your fault, Mom. This is a fucking mess. I’m calling 9-11.”

“No, Becky, I’m fine.”

“Hold this,” Becky demanded. Her mother took the towel with her right hand and held it against her cheek.

Becky ran to get her cell phone and called the cops. They arrived eight minutes later and took Becky’s mother away on a stretcher. She was stitched up and tested for internal head injuries.

Two hours later, Becky was sitting in the chair beside her mother’s hospital bed.

“Mom, you have to tell me what happened. Where’s Dad?”

“He left.”

“What do you mean, he left?”

“He’s gone, Becky,” she said.

“Mom, seriously, tell me what happened.” Becky needed to understand. Her father had never hurt her mother before, at least not physically. Verbally, yes, but never physically.

“He threw a bottle of wine,” she said.

“At you?” Anger trickled through Becky’s body.

“No, at the wall. It shattered.”

“God damnit, mom.”

“He left me, Beck,” she said. “Isn’t that enough?” Her mothers’ eyes filled with tears.

Becky’s parents had met in high school and married when they were both twenty years old. Five months later, they had Becky’s older sister, and two years later, they had Becky. For as long as she could remember, Becky’s parents had fought over money, schedules, jobs, parenting. Their relationship was toxic.

Sitting in that sterile room, staring at her mother’s bandaged face, Becky couldn’t help feeling sorry for her. She reached around the IV and linked her fingers around her mother’s wrinkly hand, wondering when she had last touched her mother; not since she was young and had to hold her mother’s hand when crossing the street.

A few weeks after the incident, Becky returned home from Jay’s, and found her mother sitting in the corner of the living room with her back to the wall and her knees pressed to her chest. A pile of papers sat beside her.

“Mom, what are you doing?”

“He wants a divorce.”

Becky expected this, but instead of feeling relief, she felt a strange pang of heartache. She joined her mother on the floor in an attempt to comfort her. When Becky’s mother lifted her head, she said, flatly, “I don’t have enough money.”

“It’ll be fine,” Becky promised. It’s exactly what her parents had always told her; not that she ever believed them.

Her mother stood, leaving the papers behind, and said, “You need to get a job, Becky. I don’t care what it is, but you need to do something.” Her mother leaned against the couch, closed her eyes, and dropped her head in shame. “I can’t pay for your shit anymore,” she said. Then she opened her eyes, dropped her arms, and drifted down the hallway.

“I have a friend who could help,” Jay offered.

“Really? What does he do?”

“He’s got a good business, and you’d do well.”

“What would I do?”

“It’s a dating service,” he said matter-of-factly.

“A dating service? What the fuck does that mean?”

“All you have to do is escort rich men to events. It’s easy and it pays. You’ll make over $400 a night; easy”

Becky felt uneasy. “I don’t think so.”

“Why not?”

“Is it safe?”

“Of course it’s safe. Forget I mentioned it. If you don’t want my suggestions, don’t ask,” he replied bitterly.

“I’m sorry,” Becky said. She let go of the spoon in her hand and touched Jay’s arm. They were both sitting in front of the TV, holding a bowl of cereal.

“Thanks, I’ll think about it, okay?” Becky said.

“You said you needed the money.”

She returned to her fruit loops and waited until the next commercial to ask, “Wouldn’t it bother you?”

“What?”

“The escort thing?”

“Why would it bother me?” he asked, serious.

“Because, I’d be going out with other men. Isn’t that kind of weird?” It was, Becky decided.

“You’d be good at, and you need the money, don’t you?”

“Yeah, I guess.” Becky took another bite of her cereal, thinking maybe he was right; she needed money.

Two weeks later, Becky found herself in the backseat of a Honda with a strange man. His name was Robert, he was a businessman, and he needed a date for a client meeting. He had requested a tall brunette with long legs and a decent ass. The night before, Jay took Becky to JC Penny’s to pick out a new dress, ultimately deciding on a short cobalt blue dress that formed a V in the back, forcing her to go braless. She felt naked and exposed in the thin fabric, but Jay had recommended it for those very reasons.

Robert’s personal driver had picked Becky up from Jay’s and now they were headed to his client meeting.

“How old are you?” Robert asked, as he brushed his hand through his sleek black hair.

“Seventeen,” Becky said.

“Twenty.”

“I’m seventeen,” she repeated.

“With me, you’re twenty,” Robert said.

“I don’t look twenty,” she said.

He ignored her. “Know anything about stocks?”

“No.”

“Great. Just smile and look pretty. If anybody asks, tell them you’re a hairdresser. You can do that, right Becky?”

“Sure.” She turned towards the window and watched as cars swished past.

It was a long night, over three hours. They sat in a private back room of a crowded restaurant, and shared a four course meal. Becky remained quiet as she ate. When somebody asked how much money she made hairdressing, she said, “fifteen an hour.” They nodded in approval and asked what she thought of Obama. Becky had said, “He’s great” and the men all laughed, before returning to work. Becky had never felt as young and inferior as she did that night, as though she were just a fixture on the wall and nothing more.

Towards the end of the dinner, right before dessert, Robert leaned over and said, “Why you don’t you give us a few minutes. Go fix yourself or something and come back in fifteen minutes.”

Becky smiled politely and excused herself from the table. She was glad to leave that room, but as she stood in the bathroom, staring at herself in the mirror, she felt nauseous. She had worn too much makeup, but Jay had encouraged it, and she was showing too much side-boob.

It disturbed her, being in a strange restaurant with a strange man, not having any say in where she went or what she did. But she obeyed, because Jay promised it was safe, and he was right, she needed the money. Did it matter where the money came from? Becky wondered, knowing the answer.

After dinner, Robert showed Becky back to the car. When they were both settled into the back seat, he pulled out a cigarette and lighter.

“Can I have one?” Becky asked.

He lit it, handed it over, and then reached for another. They rolled down their windows and breathed in the tobacco. Becky felt a sudden high. Smoking was a comfort, an addiction, and she felt at ease despite the circumstances.

“You did well,” Robert said, as he brushed his cold hand across her bare knee. Becky sat upright, suddenly alert.

“Thanks,” she said as she lifted the cigarette to the window.

“Maybe we can do this again,” he said, as he grew increasingly, uncomfortably close to Becky. She anticipated a kiss or a boob grab, as if she were on a bad date, so she scooted closer to the warm air. Instead, Robert reached into the inside pocket of his suit coat and handed over a folded stack of clean bills. Becky took the wad, pressed it into her purse, and politely thanked him.

That night, Jay insisted on counting the cash for her. He took it, walking towards his bedroom, and returned with a smile, revealing that dimple.

“He must’ve liked you, huh?”

Becky shrugged, “I guess; I didn’t do much.”

“You didn’t have to.” Jay approached Becky and latched onto her hips. “Come here, sexy.” He pulled her towards him, his breath on her cheek.

“I don’t know if I’ll do that again.” She said, as Jay kissed her cheekbone, the back of her jaw, and then her earlobe. His muscular body was wrapped tightly around her thin frame.

“It was easy, wasn’t it?” he said with a growly voice.

“Yeah, but I didn’t like it.”

He pulled back, his hands still on her waist. “What’s not to like?” He looked down on her. “You keep this up, and you’ll be making bank. It’s good business, you’ll see.”

“Is it?”

“Cash is cash, Beck, and you need it, don’t you,” he said.

She remained quiet, as the words rushed over her like the steam in a hot shower.

You need it, don’t you.

Jay resumed the kissing, and Becky discarded the words, hoping they’d disappear from her memory, but she already knew they’d resurface like a dead fish.

On her third date with Robert, she was taken to a dive bar in downtown Detroit. He held her hand, leading her through the dimly-lit room, until he found his people in the far corner. There were three guys; all dressed in suits, their coats open revealing button-up shirts and stray chest hairs. Each held a glass of brown liquor and Becky quickly learned that these guys were friends, not co-workers.

Sitting there, all done up, Becky felt like a cufflink, clinging to Robert’s arm as though her sole purpose was to look expensive. Robert and his pals urged Becky to drink so she did and the longer they stayed, the drunker she got. They indulged her; offering shots and drinks over and over again.

Becky stumbled to the bathroom, feeling as though she were being pushed from both sides. She bent down to vomit in the toilet and only when she felt capable of standing did she return. It could have been minutes or hours, Becky wasn’t sure, but the men didn’t seem to notice her absence. Robert and a friend linked arms with Becky and led her back to the car. Everything was spinning; the cars in the parking lot, the stars in the sky. Their laughter echoed, burning her ears.

Once in the backseat, Becky became hypersensitive, feeling the bass of the music in her forehead. Halfway home, Robert put his hand on Becky’s leg. He dragged it all the way up to her lacy underwear. Becky was too drunk to react, but she knew it was all wrong.

“Not okay,” she slurred.

“It’s alright, baby, it won’t hurt.”

Suddenly his hand was pressed to her mouth, shutting her up, as he yanked her underwear down, and shoved his fingers inside. It hurt, that much she knew, but she couldn’t stop him. She could hardly comprehend the events, her mind racing, and the world spinning. He continued, and then, just as quickly, he was inside her. Certain her screams, though muffled, were audible, Becky looked to the driver, his eyes fixated on the road. She struggled to push him away, but she was weak and he persisted, coming inside of her.

When the car finally stopped, Robert had buttoned up his pants and now he handed her a pile of cash. She took it, unable to comprehend what just happened. She looked again at the driver, but he was looking away as she stepped out of the car in her tiny dress.

She stood outside Jay’s door and cried.

“Beck, what’s the matter?” he said, letting her inside.

“He,” she started, but the words wouldn’t come.

“Are you hungry?” Jay asked, changing subjects.

“No,” she gasped.

“Why don’t we go sit down.”

Becky collapsed on the couch, the cold leather grazing her skin. Only then did she realize her underwear was left on the floor of the car. The tears fell faster.

“Stop crying, Beck, and tell me what’s wrong.”

After she finally said, “He raped me.”

“Oh, Becky,” he said, as he held her and rubbed the back of her head. She cried into his shoulders, the scotch attempting to crawl back up her throat.

She felt dirty and nauseous, but eventually the tears stopped and she drifted to a light sleep.

She awoke on the couch, alone, in last night’s dress, with a flannel blanket wrapped around her body. She stretched out her limbs, suddenly aware of her sore thighs. In an instant, Becky felt the weight of the previous night crushing her delicate body. She sat upright, her stomach lurching forward in an attempt to vomit, but nothing came out.

“Hey you,” Jay said casually from the open kitchen. He was dressed in a pair of sweats holding two mugs.

“I have coffee,” he said with a smile, as though it were a typical morning.

He sat on the far end of the couch and handed over the blue and green striped mug. Becky took it, and then yanked at Jay’s arm, begging him to be closer.

“We need to tell somebody,” she said with a quiet concern.

“We can’t, Beck,” he said matter-of-factly.

“He can’t do that.”

“Sure he can. He paid you.” Jay said then took a sip of coffee.

In sync with her pounding headache, Becky’s heart raced. Did that make her a prostitute? No, she didn’t sign up for that. She was an escort, nothing more.

Becky put the mug on the table and fell into Jay’s chest. With his free hand, he rubbed her shoulder and then kissed the top of her greasy hair.

Jay turned on the TV and only after three episodes of Friends did Jay say, “You might not want to hear this, but you made a killing last night.”

“What?” Becky lifted her head from his chest.

“Yeah, eleven hundred.”

“Seriously?” In an attempt to forget about the night, she’d also forgotten about the money.

“I know he shouldn’t have done that,” Jay said, “but it wasn’t so bad, was it?”

Becky pushed herself up so she was hovering over Jay. “What are you talking about?”

“I’m just saying; it’s not that big of a deal.”

“It is a big deal,” she returned, the anger building.

“Listen, Beck, I really like you. Hell, I love you, but this is something you have to do. Don’t worry about me, okay? I support you.”

“Are you kidding? I don’t want to do that ever again.”

“Beck, you need the money, and honestly, I can’t keep paying for your shit. It’s a good thing you got this gig. You can start contributing and you can get different clients, if you want; that’s not a big deal.”

“Are you serious?” Becky stood off the couch. Everything felt wrong.

“Beck, don’t get like that, okay?”

“You just said you love me. Now you want me to prostitute myself?” She couldn’t believe she’d even said it aloud.

“It’s not like that,” he said, as he stood and grabbed her hand. “You have to support yourself and your mom. I’ll be here, alright, no matter what. I’m yours, remember?”

Thousands of emotions rushed through Becky’s body like the blue dye from an MRI. She felt warm and jittery.

“But it hurt,” she admitted, as Jay let go of her sweaty hand.

“It won’t, after a while.” He wrapped his body around her, smothering her with the smell of cigarettes and coffee. “Just make sure they wear condoms,” he said. “I don’t want any guy knocking up my girl,” he snickered.

Becky looked up at Jay. His round eyes were fixed on her. He was smiling lovingly, holding her tightly, and promising her welfare. Maybe he was right; maybe it was for the best. She did need the money and Becky trusted Jay. If he was okay with it, then why wasn’t she?

“You’ll still love me?” she pleaded.

“Of course,” he promised. “It’ll be worth it, you’ll see.”

Becky closed her eyes as Jay kissed her oily forehead.

Sarah Sheppard is an MFA student at Lesley University and a book publishing professional. She writes blog posts for Global Rescue Relief, a nonprofit human rights organization that provides direct and necessary relief to human trafficking survivors. She was born and raised in Michigan, but currently resides in Somerville, MA.

Read More »

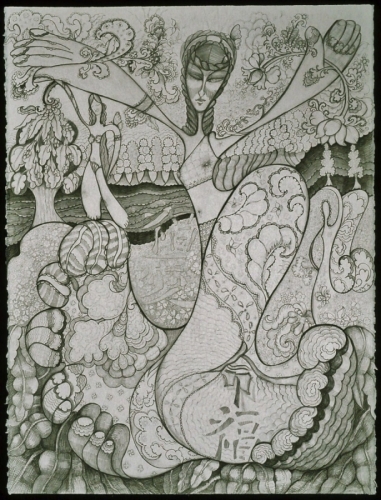

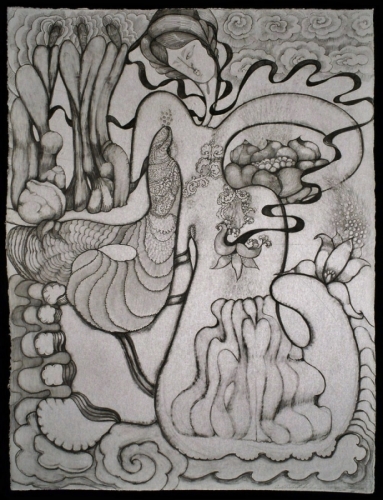

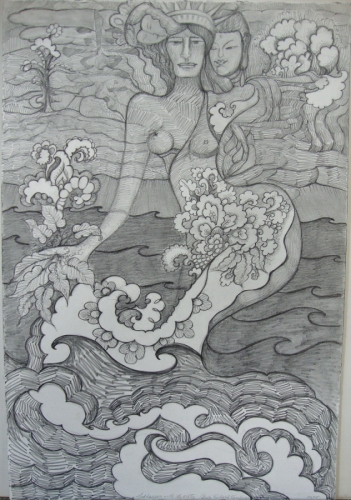

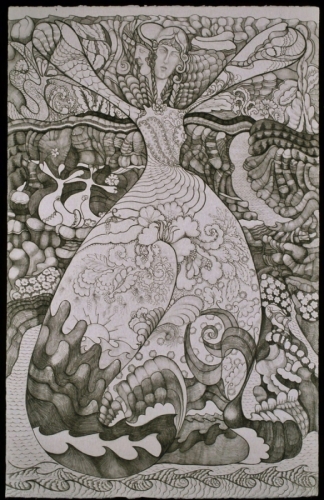

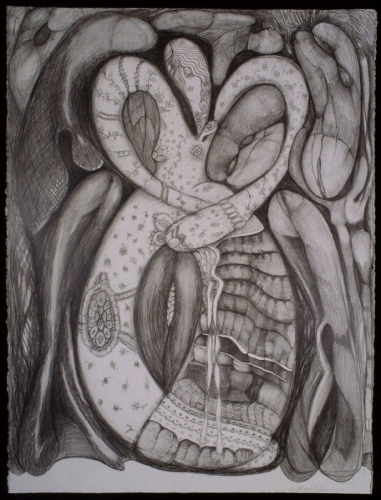

Lance Johnson is a mixed media artist born and raised in NY. As a young man raised in the Golden Age of Hip Hop, Johnson fell in love with art when he was introduced to the work of a pioneer of the Jazz Era. Romare Bearden is a heavy influence on Johnson’s artwork. “I owe a tremendous debt to the vision of Romare Bearden. I want to serve as an extension of his legacy.” Lance has shown his work in many group shows throughout NYC as well as shows in Boston and Charleston, South Carolina.

Lance Johnson is a mixed media artist born and raised in NY. As a young man raised in the Golden Age of Hip Hop, Johnson fell in love with art when he was introduced to the work of a pioneer of the Jazz Era. Romare Bearden is a heavy influence on Johnson’s artwork. “I owe a tremendous debt to the vision of Romare Bearden. I want to serve as an extension of his legacy.” Lance has shown his work in many group shows throughout NYC as well as shows in Boston and Charleston, South Carolina.

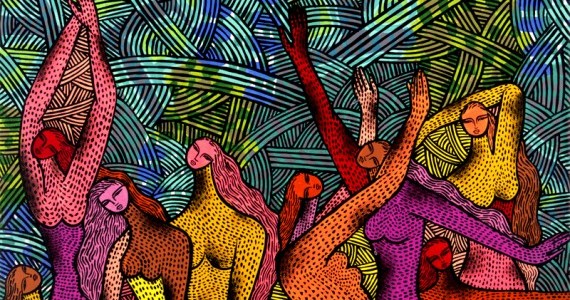

An author, performer, poet, teacher…yes to all of those titles, but more importantly Jasmine Mans is an artist…an artist who enjoys having various forums to express her thoughts, moods, opinions and a voice to speak out on behalf of others and the community around her. A recent graduate of the University of Wisconsin – Madison (2014), Jasmine received her BA in African-American Studies (Black Theory & Literature) and is the recipient of the Star Ledger – NJPAC; Arts Millennia; and (New York) Knicks Poetry Slam Scholarships and awards. However, Mans began stringing rhymes together as a middle-school student in her hometown of Newark, New Jersey. Those artistic skills were honed while attending the first performing arts high school in the nation, Newark Arts High School. A chronicle of her journey and vision, Mans released her first book, Chalk Outlines of Snow Angels in May 2012. Transcending boundaries, Chalk Outlines includes works addressing issues varying from broken relationships, fear, racism, sexuality, death and the overall human experience.

An author, performer, poet, teacher…yes to all of those titles, but more importantly Jasmine Mans is an artist…an artist who enjoys having various forums to express her thoughts, moods, opinions and a voice to speak out on behalf of others and the community around her. A recent graduate of the University of Wisconsin – Madison (2014), Jasmine received her BA in African-American Studies (Black Theory & Literature) and is the recipient of the Star Ledger – NJPAC; Arts Millennia; and (New York) Knicks Poetry Slam Scholarships and awards. However, Mans began stringing rhymes together as a middle-school student in her hometown of Newark, New Jersey. Those artistic skills were honed while attending the first performing arts high school in the nation, Newark Arts High School. A chronicle of her journey and vision, Mans released her first book, Chalk Outlines of Snow Angels in May 2012. Transcending boundaries, Chalk Outlines includes works addressing issues varying from broken relationships, fear, racism, sexuality, death and the overall human experience.

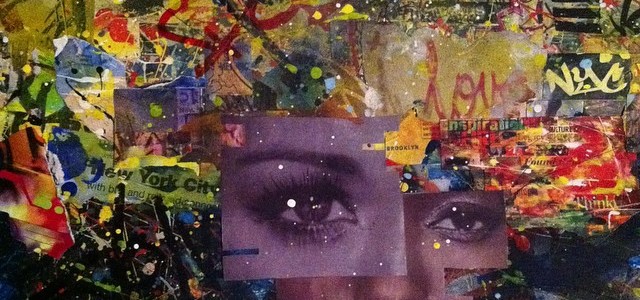

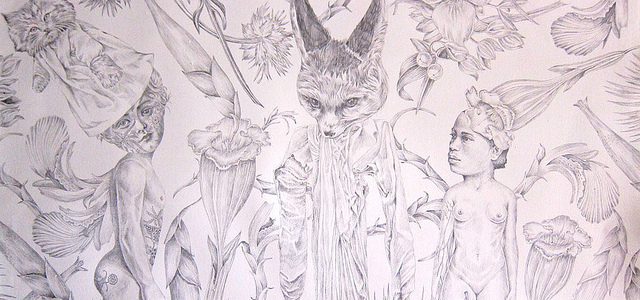

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is a poet and visual artist. Her forthcoming collection, Lighting the Shadow, will be published by Four Way Books in 2015. Currently, Griffiths teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College and lives in Brooklyn. Please visit: www.rachelelizagriffiths.com.

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is a poet and visual artist. Her forthcoming collection, Lighting the Shadow, will be published by Four Way Books in 2015. Currently, Griffiths teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College and lives in Brooklyn. Please visit: www.rachelelizagriffiths.com.

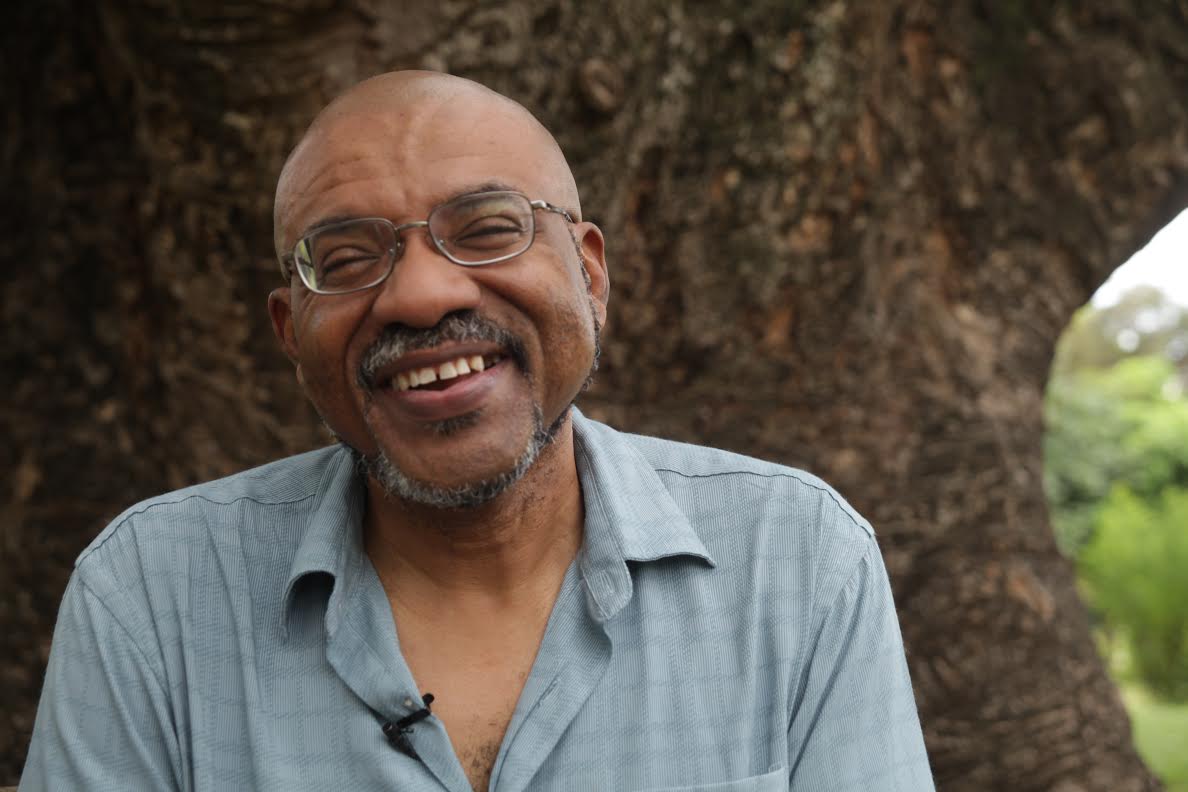

Kwame Dawes is the author of nineteen books of poetry and numerous other books of fiction, criticism, and essays. He has edited more than a dozen anthologies. His latest collection, Duppy Conqueror: New and Selected Poems (Copper Canyon), appeared in 2013. He is Glenna Luschei Editor of Prairie Schooner and teaches at the University of Nebraska and the Pacific MFA Program. He is Director of the African Poetry Book Fund and Artistic Director of

Kwame Dawes is the author of nineteen books of poetry and numerous other books of fiction, criticism, and essays. He has edited more than a dozen anthologies. His latest collection, Duppy Conqueror: New and Selected Poems (Copper Canyon), appeared in 2013. He is Glenna Luschei Editor of Prairie Schooner and teaches at the University of Nebraska and the Pacific MFA Program. He is Director of the African Poetry Book Fund and Artistic Director of

Chen Chen is the author of the chapbooks, Set the Garden on Fire (Porkbelly Press, 2015) and Kissing the Sphinx (Two of Cups Press, 2016). A Kundiman Fellow, his poems have appeared/are forthcoming in Poetry, Narrative, Drunken Boat, Ostrich Review, The Best American Poetry 2015, among others. He holds an MFA from Syracuse University and is currently a PhD candidate in English & Creative Writing at Texas Tech University. Visit him at chenchenwrites.com.

Chen Chen is the author of the chapbooks, Set the Garden on Fire (Porkbelly Press, 2015) and Kissing the Sphinx (Two of Cups Press, 2016). A Kundiman Fellow, his poems have appeared/are forthcoming in Poetry, Narrative, Drunken Boat, Ostrich Review, The Best American Poetry 2015, among others. He holds an MFA from Syracuse University and is currently a PhD candidate in English & Creative Writing at Texas Tech University. Visit him at chenchenwrites.com.

Sarah Trudgeon’s poetry has appeared in the London Review of Books, Iron Horse Literary Review, Sewanee Theological Review, Smartish Pace, and The TLS, and is forthcoming from The Nation. Her reviews have appeared in The Cincinnati Review. She was a finalist for the Poetry Foundation’s 2013 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship. She teaches part-time at the University of Miami.

Sarah Trudgeon’s poetry has appeared in the London Review of Books, Iron Horse Literary Review, Sewanee Theological Review, Smartish Pace, and The TLS, and is forthcoming from The Nation. Her reviews have appeared in The Cincinnati Review. She was a finalist for the Poetry Foundation’s 2013 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship. She teaches part-time at the University of Miami.

Erika A. Rist is a Chicago transplant looking to thrive without too-deep roots. She is a feminist activist and aspiring attorney with lofty ambitions for herself and for society. Currently, she lives in Roger’s Park with a vindictive cat named Lady.

Erika A. Rist is a Chicago transplant looking to thrive without too-deep roots. She is a feminist activist and aspiring attorney with lofty ambitions for herself and for society. Currently, she lives in Roger’s Park with a vindictive cat named Lady.