LACUNA

On trails of slash pine

and sabal palm, the sun

suggests she turn reptile

and sprawl toward water

know animal pleasure.

The wind wants to empty her

wonders if she’ll whither

to husk, involute

where language won’t go.

Inside her belly, sorrows dwell

she wants to label each one

like the wildflowers

she copied as a child–

naming the world made it real–

swamp mallow, lady slipper, trumpet vine.

Here, in the pines, she names

saw palmetto, tickseed

and the Lubber grasshoppers

that ride each other’s backs–

they slept all winter for this–

egg, then nymph, then adult,

repeat.

No name for what comes after

(encyclopedias fall short)

unless carcass.

Rot.

What is the name for her now?

Menopause–climacteric–say what she is not.

Senescence implies a coming end.

But here in the pinelands, she feels new

skin flushed with sweat.

Not hag, not fishwife, matron, or crone–

she waits on the wet season,

fecund,

conceives her lexicon.

AT PINE ISLAND

The Everglades sieve runoff into armor,

periphyton plated as a gator’s back.

Holes in oolite, like puddles on the moon,

hint at worlds beneath this one.

Beneath bayheads, scorpions creep

and under brush, the pythons sleep.

Surveyors drive stakes along the road,

marks for mowers that daily speak

with sharp, sweeping tongues

these thickets into poetry.

Men rose rapine from the sea

laid roads and tracks,

drew acreages and platts.

Architects of imagined space,

they carved drain and swale

from Disney to the mangrove sea:

Florida, but as they meant her to be.

And if they looked away?

She beat them back with flails—

green on sun-thinned walls—

laid waste whole cities with water.

So the men fight harder.

Their machines dredge and fill

utopic maps of want, cement the veil

between asleep and awake.

I see you, killing men,

holding back storm and vine—

but my words flow deeper than fear,

a song you can’t contain:

I am the stake

and the wilderness it keeps at bay,

the river of grass and the sea,

I’ll sound until there’s nothing left to save,

hymn of what might still be.

ON THE OLD INGRAHAM HIGHWAY

When the world stopped seeing me,

I burned from the inside out, like grasses on the roadside,

deep orange thrust, saw-blade-sharp if stroked the wrong way.

When the world stopped hearing me,

I began to lose words. I let the wind empty me

till my voice became a tiny chirp, louder at dusk and dawn.

When the world forgot the taste of me, the texture of my skin,

my body hardened like the spiked head of a thistle,

purpled and angry. Then, all that was left was to walk into the grasslands–

Clouds drifted over the far cypress domes–

I let myself sink in marl, where the water hides,

until the Earth caught me. Now I am queen

of the frogs and insects, the tiniest fishes.

I use my last word to call the blackbirds to me;

they dart and sing in the mystery of my long shadow–

the days grow heavier, the earth darker.

We wait on the wide, grassy slough for the thing that will fill us—

they say when the water comes, it will not come gently.

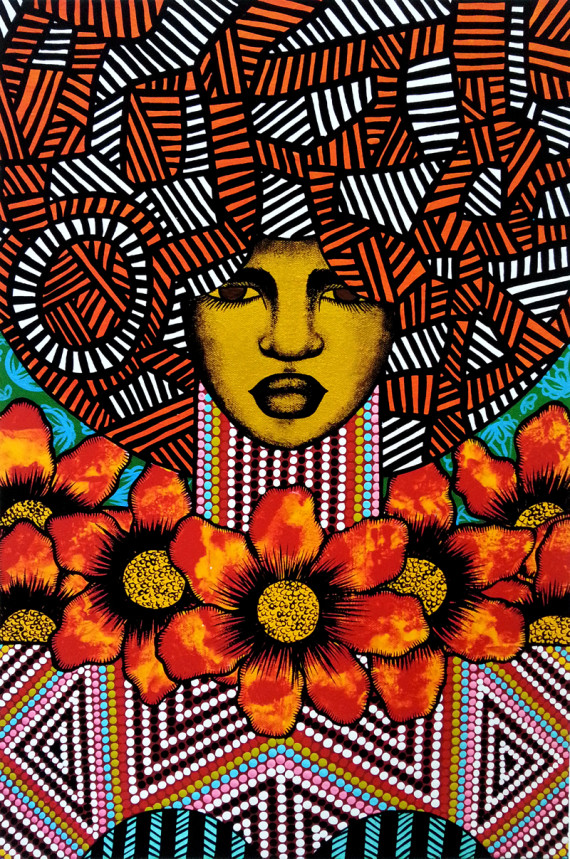

Anne Jennings Paris is a writer, a visual artist, and a mother. She has lived in the Portland, Oregon area for the past 15 years, and she is native of Gainesville, Florida. Her recent work looks at the human and non-human ecology of threatened landscapes and watersheds.

Related Posts

« TWO POEMS & THREE PHOTOS – MICHAEL MONTLACK BASHO IN AMERICA – Sander Zulauf »