As the throng assembles, they note the colorful expressions of each hungry gaze. Rich, vivid, stained like the reds, blues, greens, and purples of the window behind the towering pulpit. In its center, the cross blazes white, its presence signifying God’s merciful grace and Christ’s ascension. And above, a large emblem reads in French, “Jesus Saves.” But the two men, standing between the mint green baptismal pool and the altar feign indifference and ignorance. Though under close scrutiny, their brows furrow in fear and anticipation of what looms in the sanctuary. The persecution has begun.

My earliest memory of Saturday mornings is me sitting between my mother’s scrawny thighs on the carpet, now dusty and spattered from years of clunky boots and soiled shoes stomping across its coarse nylon hairs. Legs crossed Navaho style, I’d patiently but painfully wait for the brushing bristles to attack the coiled locks of my curly hair. Then my mother would dress me in the frilliest confection—lace, tulle, cotton, spandex, fishnet stockings, and black patent leather, click-clacking shoes—and shove me out of the front door. This was the routine every Saturday as we trudged our way to morning service.

19 years have passed since that morning, our family of seven bunched together in the banana mobile, quietly suffering the 25-minute drive to Salem Seventh- Day Adventist Church. But the church remains the same. Except for the carpet. Gum stains the over trodden foot path. Heavy footprints lay imbedded in the red matting. The runner now lay squalid and vulnerable to stilettos, Mary Janes, and oxfords. But the benches, the pews that support backs and backsides are still vibrant. Though infested with holes and riddled with pen markings, they are carmine melded with crimson cherries, the bloodiest stain of red I’ve ever seen. They’ve stood witness to many events: wedding ceremonies, funeral processions, church proceedings, family functions. And this evening, an inquisition.

From the left side of the sanctuary, I am silent. Like the others, I watch the pastor’s wary expression. Mechanically, he smiles to Claude, his faithful confidant and voice of reason. Together, they stare at the large, hostile crowd. Together they stare, as two sheep awaiting slaughter. No one misses the streams of perspiration winding past their temples. Nor the frown that passes from one’s lips to the other’s flushed cheeks. And as the pastor and the church Elder whisper to each other, I know that this sanctuary is no refuge for the lost.

“I am grateful for your patience,” begins Claude. “But before this meeting can come to a close, there is one more matter to be discussed.” As he runs through a litany of meaningless words, my eyes gravitate to two distinctive women. Both beautiful and petite. Both angry and defensive. We are going to dissect them, piecing their lives in fragments.

“We forbid you,” continues Claude. “Not because we think that those of the world don’t deserve love. They are children of God as well. But we forbid you to engage in such a manner BECAUSE THE BIBLE SAYS SO!” he booms. They’ve wielded this weapon for years: “According to the bible,” “the scripture reads,” “thou shall not.” Armaments to keep us fastened to their red pews.

“Tonight we must take a measure. Because two women have not only sinned against each other, but also against God. Children, you must remember where you walk! Nothing remains hidden.” As the pastor continues, my eyes wander once more toward these two women, their prideful backs rigid, erect from shame and disgrace. Though their names have yet to be mentioned, they wear their scarlet letters, braced across their sunken chests. I wonder at their stupidity. Their demise, how they’ve fallen from grace. It only takes one act. A lie. A kiss. And then pure, unadulterated sin.

“But Pastor, she was with him first,” shouts the first witness. “He was her first love. Her first boyfriend. But that one,” she spits with venom, “stole him away under the guise of concern. She should be punished!”

“You don’t understand!” interrupts another witness. “You think your damn niece is innocent. First love my ass! She has a history of ‘first loves’ if I’m not mistaken. There was Mitchell, the man with a girl friend. Julian, the other man with a girl friend. Then Luis the married— ”

“Enough!” Claude barks, slamming his clinched fist against the wooden podium. “We’re not here to discuss their personal lives. The reality is that two women, in this church, intentionally, have been dating the same man. And to make matters worse, he is an outsider. He’s not even baptized!” Suddenly, the crowd is frenzied. Like persecutors, they gleefully gloat as their victims concede to death.

“What’s it to you Claude?” one man quips, pointing his index finger shrewdly at the Elder’s nose. “It’s not the first time this has happened in Salem. Why, I remember just last year, a similar incident took place. And you did nothing about it.”

“Yea! You did nothing about it!”

“They never do anything about…ANYTHING if you ask me”

“Well I say you censure both women for two years. God knows what it takes to keep a man’s eyes from wandering”

“Heavens! Do you hear what she’s implying?”

As the members sit babbling and deliberating amongst themselves, I think about this man, this Don Juan, Casanova, womanizing scoundrel who’d divided the women in Salem. And I smile.

The first time he’d puckered his lips against my pouty pink folds, we were in the backseat of his Toyota truck. His shirt creased and unbuttoned, he would lead me straight to hell. I, with my legs straddling his waste. I, kissing the beating pulse at the side of his graceful neck. Wanted to go. Straight to hell. But I was only 17. Sometime later, as I shifted my weight to one side, ready to end what we’d just begun, he’d placed his delicate fingers across my warm cheeks. “You can hide it all you want,” he whispered. But you’re a monster. You all are.”

He stood correct as we decided their fates that evening. All of us, artfully dressed in demure frocks and wide-brimmed hats. The women clutching their hymnals. The men, their King James Version bibles. We sinned while we sang and prayed. We sinned and delivered are judgments.

“ Six months of censure, no communion, no church activities. No positions,” repeated the pastor. The two would be ostracized, quarantined like the ill, separated from the righteous.

“All in favor, please raise your right hand.” As the crowd sat still, my hand was the first of 57 to sanction their penance. I suppose I was relieved. They’d never known about me. Or maybe the two women had been enough for that evening. Either way, I wanted to burn.

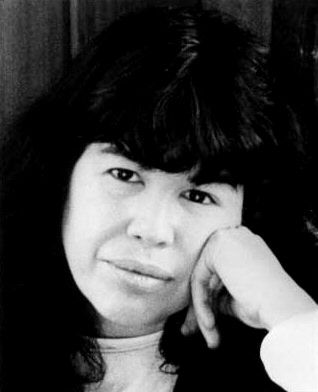

Landzy Theodore is a graduate of Bloomfield College, where she studied creative writing.

Landzy Theodore is a graduate of Bloomfield College, where she studied creative writing.

Read More »