Before today, it had never really occurred to me that cousin Emily was a normal person. No; that sounds wrong. She was too normal, that was the problem: a middle-aged woman with carefully-straightened hair, Christian husband, Christian kids — not Jewish like us. Maybe it was all to please her mother, a blonde and blue-eyed shiksa who had whittled her Jewish daughter into her own image until nothing ethnic remained; Dad says even Emily’s nose was fake, surgically flattened as soon as she was old enough. There seemed something sad about her life in Maine, where they ate lobster every night and lived quietly behind a white picket fence.

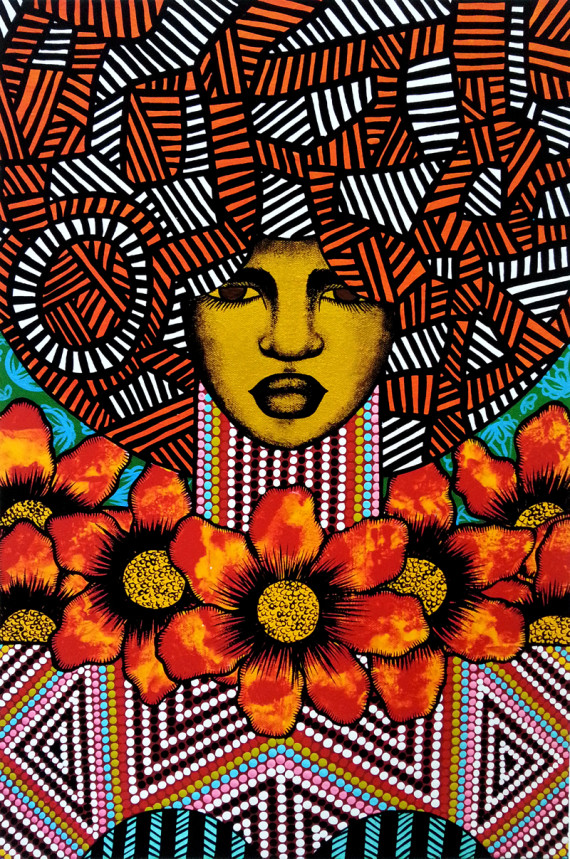

But today Emily is smiling, happy like never before. Some women crumble after a divorce, unsure of themselves, but Emily has blossomed into a person she’d never had the courage to be. Holding hands with Karen at the brunch table, Emily seems like someone else, someone bigger than life. Even her hair is bigger; tentative sprigs of frizz have sprung free in New York’s August humidity. It’s funny: Emily’s old home with her husband was alien and WASPy, her three kids obedient like mice – a take-off-your-shoes-before-entering kind of thing. But this Emily, eating a bagel and lox beside her girlfriend, feels like family.

Emily takes the reins of the conversation, telling the story of how they’d met (at the law firm where she worked). There are some omissions: whether she’d met Karen before or after leaving John; why she’d stayed with him so long (was it for the sake of her mother, or had it really been an honest mistake? Can you just wake up in your forties, suddenly gay? Or did she think that she could iron herself straight as easily as she had done her hair?).

There’s an old joke: two Jews, each with a nose job, marry. Then, when a baby comes along, it has a nose like a Macaw — and that’s God’s way of saying “booga booga”. The moral: If you try to change who you are, it always comes back to bite you in the ass.

In the kitchen, Mom and Grandma are huddled in private conversation:

“What do you think of Karen?”

“She’s a nice girl. A lawyer. John would have liked her.”

“Poor Betty. At least she got some grandchildren before it happened,” Mom says. She turns to me. “Don’t you get any ideas. You, marry a man. Better to marry a goy, even, than to get into all of this mishegas.” After a thoughtful pause, she adds, “It’s worse when it’s your own kid, isn’t it? Poor Betty.”

She pauses again as if waiting for an answer, but the conversation doesn’t call for a response, and they continue without one.

When they leave, packing into a cab after the usual heartfelt goodbyes, Grandpa turns to Mom with a look in his eye of something like pride. “She’s the third one in my family.”

“The third what?” she asks.

“Lesbian,” he declares. “It was Sylvia, then Muriel, and now her.” He nods to himself, satisfied by the list. “Three suicides too – Richie and Gladys and David.”

How absurd to count such a thing – as if lesbians were as bizarre as suicides, something to be classified and numbered.

Three lesbians in the family. Well Mom, like it or not, pretty soon there’s going to be a fourth.

Tess Tabak is a writer, filmmaker, and co-editor of The Furious Gazelle. She is a recent graduate of the Purchase College fiction program. Her short story, “The Miraculous,” will appear in the upcoming anthology Athena’s Daughter’s II from Silence in the Library. Tess can be reached at tesstabak@gmail.com or on twitter @tesstabak.

Related Posts

« Things Stuck in Other Things Where They Don’t Belong — Chen Chen BEFORE YOU – Kwame Dawes »