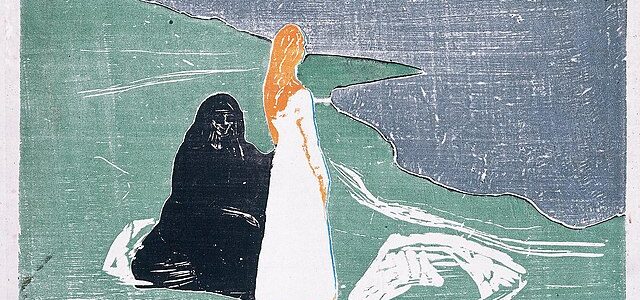

Inspired in part by Annibale Carraci’s painting The Bean Eater (c. 1580-1590) and Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s fruit and vegetable “portraits” (c. 1590)

“Boil us, bake us, put us in a pot!”

I heard this emanating from the kitchen one evening about a month after I had moved into my house, which had been Mrs. Vincarelli’s throughout my childhood. Her children had all moved to Florida and were happy to sell to someone they knew, someone born and raised in the neighborhood. So here I was…hearing voices in what still felt like someone else’s house.

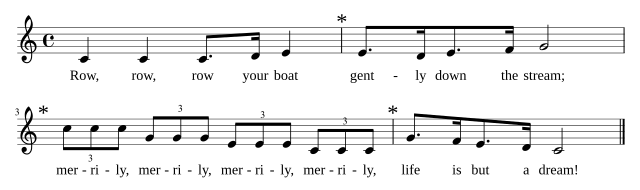

“Boil us, bake us, put us in a pot!”

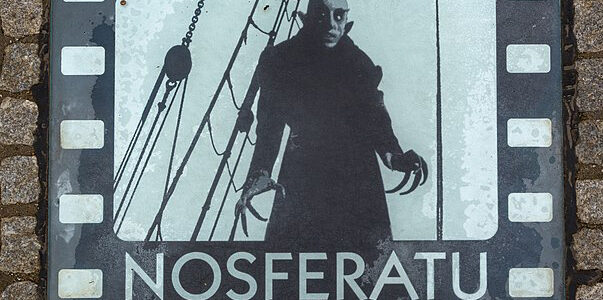

A merry chant, not menacing, but then again, strange voices in one’s kitchen – especially after sundown—strike me as unsettling.

I entered the kitchen. Floating just above the stove was a figure, now a man, now a woman, sometimes a little of both, about two feet tall. Now comes the weird part: the creature consisted of swirling beans…cannellini, ceci, lenticchie, black beans, white beans, red beans, streaky borlotti. Coalescing and dispersing, reforming in slightly different guises, periodically saying:

“Boil us, bake us, put us in a pot!”

I goggled at the bean-thing (apparition?). It seemed satisfied to dance above the stove, while gesturing at my pantry. Flummoxed, unnerved, I called my uncle Tony.

Uncle Tony is the self-proclaimed head of the family, now that my grandparents are dead. The rest of us humor him, especially when he gets nostalgic for Italian places he has never visited, but we have to admit that in times of crisis Uncle Tony is our go-to guy. He is what we call a “saputo,” a “know-it-all,” at least in the Tuscan peasant dialect that our forebears spoke. Irritating at times, sure, but usually with a kernel of information on obscure topics that was handy when we needed it. Like precisely now, for instance.

“Hey, Uncle Tony,” I said. “Please, you gotta come over, right away.”

“Frankie,” he said. “You sure it can’t wait? You know the Nets are on…”

“Got something even better,” I said. “A…ghost or something, dancing in my kitchen.”

We prank each other a lot in our family, so it took Uncle Tony a while to believe me. He lives four blocks away, so he arrived within minutes.

“Holy shit!” he said, inspecting the bean-figure as it capered.

“Do you think it’s a ghost?” I said. “Mrs. Vincarelli come back? ”

Uncle Tony shook his head.

“No way,” he said. “She was mean but efficient. She wouldn’t bother coming back as a haunt once her time here was done.”

(“Boil us, bake us, put us in a pot!”)

He was watching the bean-arms.

“What you got in your pantry?” he asked.

“What?” I said. “Right now you’re hungry?”

“No, no…but we’re gonna have to check what you got in there.”

He rummaged through the shelves, which were well stocked since I had recently moved in, and I like to cook.

“Ah hah!,” said Uncle Tony, in triumph. “Look at these!”

He was waving a can of beans in each hand.

“So what? Your point is…?”

“Rispetto,” he said, and I knew a lesson was coming because he always sprinkled Italian into his speech whenever he started lecturing, even though he was born in New Jersey just like the rest of us.

“Alora! You know what we’re called back home in Tuscany?”

I always sigh when I hear Uncle Tony describe Tuscany (the hills around Pistoia to be exact) as “home” when three generations of our family have been raised within a few miles of this or that exit along the Garden State Parkway. But I play along because he is not entirely wrong either.

“Sure, the mangiafagioli,” I say (even I know this much Italian). “The bean-eaters.”

“Precisamente! We were mezzadri, sharecroppers, and since all we could afford was beans, we became bean-experts. We knew our beans!”

I arched an eyebrow but kept listening.

“Remember the stories your nonna used to tell, about her mother, your bisnonna, arriving in the States?”

And then suddenly I did remember!

“Yeah,” I said. “She had only the clothes on her back, and a little cardboard suitcase…but in that suitcase was a treasure from home…a bag of beans…”

“Cannellini,” said Uncle Tony, his eyes focused faraway, as if he had been there himself.

(“Boil us, bake us, put us in a pot!”)

The vision faded, for me at least.

“Okay,” I said. “But I don’t get how great-grandma’s bag of beans connects to ….whatever this thing is that’s doing calisthenics in my kitchen.”

“Beans in cans are fine,” said Uncle Tony, in full saputo mode. “We’re in America now, life is busy, no time to cook over the forno like in the Old Country, not every day. Everyone understands…but now and then, every now and then, you gotta go old school, I mean back to the original.”

(“Boil us, bake us, put us in a pot!”)

I still did not understand.

“Beans, like those,” said Uncle Tony, pointing at the legume-figure. “You have to select them with care, clean them, sort them, soak them overnight. You need to boil them slowly, stirring (that’s mescolare, I think) and tasting. Mix in your sage and your thyme, a little onion, dash of pepper, drop of best olive oil.”

Comprehension dawned at last.

“Honoring the beans,” I said.

The beans grew to a manikin three feet tall, saluted, and vanished.

So that’s it. Once a month or so, I prepare beans the old-fashioned way, and the spirit of the bean is content. I sense its presence on the edge of vision, maybe I hear its words early on a Saturday morning. That’s all good: my hearth is complete now, protected and satisfied.

On the other hand, my hot water heater is wonky. It moans in the basement but that is purely mechanical (I think). I mean, we had no running water in Tuscany, let alone heated water, so I cannot imagine there’s a guardian spirit of plumbing or whatever to appease.

Still, just to be sure, I am calling Uncle Tony this weekend.

Daniel A. Rabuzzi (he / his) has had two novels, five short stories, 30 poems, and nearly 50 essays / articles published (www.danielarabuzzi.com). He lived eight years in Norway, Germany and France. He earned degrees in the study of folklore & mythology and European history. He lives in New York City with his artistic partner & spouse, the woodcarver Deborah A. Mills (deborahmillswoodcarving@earthlink.net)

Read More »

Patricia Carragon is known throughout New York City as an energetic and indefatigable writer/poet/curator who runs the long-running and popular Brownstone Poets Reading Series, promoting poetry nationally and internationally. She is the editor of the online journal, Sense and Sensibility Haiku, and an emerging photographer. Her work is widely published and she is the author of the The Cupcake Chronicles (Poets Wear Prada, 2017); a haiku/photography chapbook on cats, Meowku (Poets Wear Prada, 2019); and her debut novel, Angel Fire (Alien Buddha Press, 2020). Her poetry collections comprise Innocence (Finishing Line Press, 2017), Urban Haiku and More (Fierce Grace Press, 2010), and Journey to the Center of My Mind (Rogue Scholars Press, 2005). Her latest jazz poetry collection is Stranger on the Shore (Human Error Publishing, 2026).

Patricia Carragon is known throughout New York City as an energetic and indefatigable writer/poet/curator who runs the long-running and popular Brownstone Poets Reading Series, promoting poetry nationally and internationally. She is the editor of the online journal, Sense and Sensibility Haiku, and an emerging photographer. Her work is widely published and she is the author of the The Cupcake Chronicles (Poets Wear Prada, 2017); a haiku/photography chapbook on cats, Meowku (Poets Wear Prada, 2019); and her debut novel, Angel Fire (Alien Buddha Press, 2020). Her poetry collections comprise Innocence (Finishing Line Press, 2017), Urban Haiku and More (Fierce Grace Press, 2010), and Journey to the Center of My Mind (Rogue Scholars Press, 2005). Her latest jazz poetry collection is Stranger on the Shore (Human Error Publishing, 2026).

Marc Egnal is a retired professor, living in Toronto, and author of several books on US and Canadian history. His stories have been published in Freedom Fiction Journal and Lowestoft Chronicle. When not writing, he can be found walking my French bulldog, Holden, or playing with grandchildren.

Marc Egnal is a retired professor, living in Toronto, and author of several books on US and Canadian history. His stories have been published in Freedom Fiction Journal and Lowestoft Chronicle. When not writing, he can be found walking my French bulldog, Holden, or playing with grandchildren.

Paul Genega’s seventh full-length collection, Outtakes: New and Selected Poems 1975-2023, was published by Salmon Poetry in December, 2023. Over a long career, his poems have appeared in scores of magazines and journals, including Poetry, New York Quarterly, The Nation and North American Review. He is Professor Emeritus at Bloomfield College of Montclair State University in New Jersey where he founded the creative writing program, taught literature and writing, chaired the Humanities Division, and served as Chair of Faculty. Visit him at www.paulgenega.com.

Paul Genega’s seventh full-length collection, Outtakes: New and Selected Poems 1975-2023, was published by Salmon Poetry in December, 2023. Over a long career, his poems have appeared in scores of magazines and journals, including Poetry, New York Quarterly, The Nation and North American Review. He is Professor Emeritus at Bloomfield College of Montclair State University in New Jersey where he founded the creative writing program, taught literature and writing, chaired the Humanities Division, and served as Chair of Faculty. Visit him at www.paulgenega.com.

Megha Sood is an award-winning Asian-American author, poet, editor, and literary activist from New Jersey. Literary Partner with “Life in Quarantine”, at Stanford University. Her four poetry collections include the award-winning (My Body Lives Like a Threat, FlowerSong Press, 2022), (My Body is Not an Apology, FinishingLine Press, 2021), and ( Language of the Wound is Love, FlowerSong Press, 2025). She has received support from VONA, Pen Women, Dodge Foundation, Kundiman, and Martha’s Vineyard Writing Institute. Her 900+ works have been featured in print, online journals, public exhibits, and anthologies including the Poetry Society of New York, MS Magazine, NYPL, Pen Magazine by American Pen Women, PBS American Portrait, NPR, WNYC Studio, etc, and numerous universities including Stanford University, Howard University, George Mason, Columbia. Her poems and anthology The Medusa Project have been selected to be sent to the moon in 2025 as part of the historical LunarCodex Project in collaboration with NASA/SpaceX. Find her at https://linktr.ee/meghasood

Megha Sood is an award-winning Asian-American author, poet, editor, and literary activist from New Jersey. Literary Partner with “Life in Quarantine”, at Stanford University. Her four poetry collections include the award-winning (My Body Lives Like a Threat, FlowerSong Press, 2022), (My Body is Not an Apology, FinishingLine Press, 2021), and ( Language of the Wound is Love, FlowerSong Press, 2025). She has received support from VONA, Pen Women, Dodge Foundation, Kundiman, and Martha’s Vineyard Writing Institute. Her 900+ works have been featured in print, online journals, public exhibits, and anthologies including the Poetry Society of New York, MS Magazine, NYPL, Pen Magazine by American Pen Women, PBS American Portrait, NPR, WNYC Studio, etc, and numerous universities including Stanford University, Howard University, George Mason, Columbia. Her poems and anthology The Medusa Project have been selected to be sent to the moon in 2025 as part of the historical LunarCodex Project in collaboration with NASA/SpaceX. Find her at https://linktr.ee/meghasood