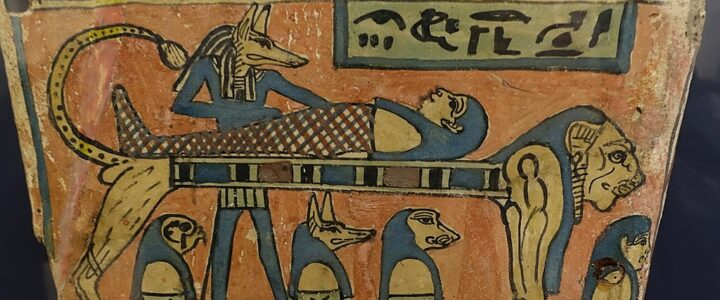

He was enormous, stretched, gold cat-eyes, the skull of a dog, crisp, beneath which the long mouth lay, all under a ceremonial gold braid, surrounded by erect dog ears; each of them drawn to a point, and he was all of black, sable black.

He came to me in the dead of night, and said to me without so much as a handshake, “Let’s go out walking, you and I.”

Does one do this with strangers? Almost never. I say, I have a soul. Sleeping in a single bed, every night, is never easy. Especially one with sides.

I took a sleeping pill. I always do. One, not two, and he approached me. I do not like waking up in the night. I have to pitch my way back into consciousness. He had a gold walking stick. The doorway led to a hallway.

Naked, yes, except for the skirt covering a slender waist, descended from which, arrow shaped legs converged on bare feet. The base of the torso itself as delicate as wind chimes. He had a demure behind, lovely, yes, as a woman’s breasts. I was abrupt. “You’re a jackal.”

He stared at me. He did suggest a jackal. “My name is Anubis, the God of embalming.”

There was no particular accent to his voice, either that of a boy, an old man, even, or somewhere between a woman and a toddler. He spoke in whispers. In fact, he churned my blood, urged it.

I have always understood likeness for what it is. We all do. Imagery is a sweet sap. Even the rain collects it.

It had been raining, yes. The glass on my window was melted, into rivulets. The rivulets resembled diamonds to me. Was I in an apartment? Really? Or somewhere else? A death chamber, I thought, I had to think. In fact, it had rained, several days now. I could smell mildew, which comes from damp. There are those who suggest sunlight is a brighter form of gold.

I sat up. Yes, he approached, took my comforter down, examined my body, in its sleeping gown. Was it the gown my mother had worn, that I’d kept with me–after her death–if only a thought?

It brought to me the tenor of her face. She’d perished–if I remembered correctly–swirling in a current that has no face. I thought it was natural.

“You don’t look like a dead person,” I said.

“I take care of the dead. How would I be anyone else?”

I did not want my mother with us. You understand. You see, Anubis stroked my breasts, I felt my milk inside of me, one drink, then another. I rose, left my room, its reign of sleepy terror. I quivered, under his breath, his scent. They were flowers, orchids, the uncertain smell of certain roses stained scarlet. These stirred me.

“Come with me now,” he said. “I will take you where the sun is all things. There is a valley, yes, where stone reflects stars.” To amplify himself, Anubis removed his belt, pants, untucked the many folds, revealed his striking anatomy. We sank to the floor. He lay beside me, turned toward him. I was penetrated. My soul–he said this was the KA, the embodiment–cried out. I could not live without bounds.

“This,” he said, “bonds you. Now we will travel. The distance isn’t far.”

Was this only an instant? I took hold of him by the small of his back. We crossed, we two, through shadow no void could penetrate, within which suns might lie—myself, now, holding his thigh. Anubis beckoned, as a female would beckon. I held him. We flew uncertain distances, but there was no travel.

We left this house, it was not a house, that was a lie—I hated it, precious little faces, ghost-like, grotesque, in beds like mine, secured–against what?–not one of them familiar.

Clouds gathered us, we loomed as we turned, I could see marks now wind had left in the sand below us, a great reach of sand, mountains, forms made of hills, motion, caught in their own memory of restless breath, and within them–as if a seam–river.

Illumination. Daybreak. Dark chased into shadow. We were finished with uncertainty. Unfathomed in my mind, a new place.

“This is yours,” he said, his voice–I would guess—I’d heard, countless times, every walk I’d taken, words I’d spoken, yes, even to the many strangers I’d passed, here and there, those I could not recall, how many and how few, vanished from sight, that my life might not be overburdened.

We settled into a grove. It bore no resemblance to sleep, to turning. “Do not caress me,” he said. “I am the way.” I had touched him. He lay down in the sand, on his belly. There was sand on his legs. “Without time,” he said to me, “there is no fear.”

He exposed me, totally, again. Buck naked, we waded into the current, Anubis pulled away from me, with such long strokes, his head bright. We found ourselves in a green pool. On the bank of this pool, there was a corpse.

There was no odor, the eyes, both white, the dark interior, ring, the ring of curiosity, absent, the dark point scoured, annihilated. Anubis took hold of its leg, drew it into the water, where it vanished.

“Why did you do this?” I said. Was I talking to myself–or to his KA? And were they separable?

“This man was ordinary. You are not ordinary. You know that. We put our organs in jars. We leave others to their fates. Things will become clear to you, if you only look. The afternoon is fresh.”

“But it’s only morning.” Why did I say this? Why did I insist?

“They are the same. Only you are different, when each of these things happens.” His voice had deepened, his dark body now in contrast to the rash sunlight. We heard nothing. Only our voices. There was no corpse to mourn.

“You won’t leave me,” I said to him, suddenly. I don’t know why. I leaned, kissed him. He kneeled in the sand, over me. His mouth felt man-like, I caught the edge of his tongue in my teeth, I felt his shoulders. I caught my finger up in each of his bright strands of braid.

“Morning is when our senses dream,” he said. “This man, this corpse, is still in your eyes. This is another form of birth. There are others. They lead.”

Anubis put his fingers to his lips, he felt them with his tongue. I was ashamed of my appetite. I hungered. What did I miss?

“Everything happens once. There are no repetitions.”

“Morning always happens,” I insisted.

“This is your imagination. Teeming with what you know. Imagination weaves. Talk is a wasp.”

He stood up now. “This river, all these fish, the corpse, have receded, many times. They replenish us. I, Anubis, manage this curtain of forms, hollow, only in remembrance. We cannot cling.

“Men, women–these are narrow distances, between which nothing is forgotten. Vivid, yes, lies, if you will, of infatuation. They have no lasting weight, beyond the uncertain shape of the dead—may I call you, Anna? No, it is not you, the name. An unwavering, constant shape. We subside beyond our names. The soul, yes, the KA, is general. The water withdraws, the seeds that infest, waters, currents, carry them, and they follow. The current does not bear wishes. It carries them. It is wicked.”

Anna was never my name. “You’re lying to me,” I said. I did care.

“You are real. Not your name, Anna.”

“Then, who am I?”

“You should know. You will know.”

We walked the river bank, a tributary, it fed a larger river, Anubis walked among the shallows, up to his ankles, mud pocks drew my smaller feet down, I fought to raise them, the sand on the bank, afterwards, only coated my feet. I resembled sand, walking. “Where are we going now?” I asked. I had to. I was dizzy. My stomach upset.

“On a boat ride. A journey, if you must. Minutes. Can you tolerate minutes?”

“But where?” I saw a child. A boy, sitting on a bank. Under a cluster of palms. I felt the sun penetrate my skin, minimal shade, the sun higher, I think I was happy with Anubis. A single stump of palm, now—this ringed, hard trunk—had been sunk into the sand, the water about it shattering diamond, this mirage so intense, the high points of it made me want to close my eyes, shut them. When you close your window.

I remarked the white sail of a felucca in the distance, little more than a skiff, its shadows blinking. The sail billowed. The child smiled. Not far behind, I saw an old man smile, without his beginning teeth. These teeth lost, in skin layered like onion, the open beauty of the boy had come, at once, to this concealment of what we call age. In honor of the world. “Our wake is our awakening,” Anubis said, “to what shall happen.”

The uncoiled line, a single line, trailed in the water. Anubis let the boom out, waited for a breeze. We were adrift. I leaned over the side and saw the bottom, clear, immaculate, an apparition of glass merely, only for a time.

Then green began to cover the pebbles, in sand, mud, now, what had once been smoothed and now agitated, there was nothing but sky, cloud, on top of this, I thought I was blind. Anubis shook his head, to say, no. Anubis held the tiller and put his arm around me.

We glided along the shore, bent, wound, turned onto the greater depth of the river itself, the shore less than nothing now, small, in the haze, away, no longer distinct, part of us. Foreign, even. I saw, then, the great stone formations, the greater landscape of all this. Our one day. I could make them out, in the haze. But was it haze? Gazing across the splintered wood of the boat itself, I saw my life flow in this hollow morning water, sun, on my arms and forehead. Did being a wife, an object, a trial, an irritation, make you less than anything else?

I wanted to think Anubis was perfect, in every definition of perfect, molded, yes, adorned, a mystery, not what we commonly think of as merely human. He read my thoughts. I knew this. Did a good husband come to you, for your inmost perceptions, ever? And did he shield himself from what is inevitably deep, hostile, a life-defiance that burns, as sun does? Women destroy those who would bring desire, turn to their children, away from their boyish husband. A badly shattered dream.

“What?” I said.

I wanted to settle this moment into passages I would understand.

“There is only nature,” Anubis said this, as if answering. He wiped his muzzle with his hand. “Anna, we can’t know why we are, why we weren’t before this, we are so entire, why we will not be, on a wisp of current. We know this moment. Our time, we call it. It shifts. We are, and will be, the same. Look at anything.

He stared. Frightened me now. There were no footprints that I could see, anywhere. We pulled toward the vacant shore. An ibis, in a tree, yes, white wings folded up, razor sharp beak, gleaming, each eye a dark fleck in sun, the ibis–if I left it behind–would not age. In a day, in a week. In a score of years, divided by the illusion of decades. Because I would not see it again, it wouldn’t rot, would it, a cusp of nothing. But what was it, now, then? And to what end?

Anubis brought a scythe up, out of the shallow hold of the felucca, I had not noticed it, in the time we’d been in the boat. He reached, cut a coconut away from the palm. It wasn’t a coconut. It was dates, these were date palms–hiding their odors until I bit into them. If there was rain, the sand would soak it up, Anubis handed me each date, I ate only one. “Your pleasures will be limited,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

“We will watch the sun descend,” he said. His big dog teeth gleamed in matchless yellow, his mouth a glaze, a hammering of light too generous. I looked at the sand, the lovely, hovering, broken mountain shapes about us, dancing atmospheric design, and I felt lost, lonely. An inhuman unsettling transport. Carried, plunged deep. “Come. This is your seeding time. We, you, I, have people to bury.”

“Where?” I said.

“Wishes don’t matter. This is only a moment. It does not need the weight of yourself.”

The ibis spread its wings, caught the air, cast itself, off the palm, worked its way out, over the horizon. Was something there that might not be found? The ibis soared, a ship, over our own white mast, over the horizon itself, one of many, its vistas awash, height, distance, illusion, these things didn’t matter in the least.

“He carries all souls, on his back,” Anubis said, “as I do. And Earth creates another of each. Each to each.”

The felucca turned in a swathe, took us back, to our first shore.

I saw the very mark our prow had left sometime before, in the sand. The boy we met before stood waiting for us. I thought I knew him, perhaps, what might pass for his mother, that once lovely, intent face, the uncertain swelling in her waist distracted, alongside the child-like fury of the river itself, only stilled for an instant, her long, shining, covering ended in a seam, as the boy took our bow line.

Now the sun bore down heavily on the horizon–which would swallow it, extinguish it. “Hurry, now,” Anubis said to me. “Hurry.” The boy’s face said the same.

“We’re going to the Valley of Kings now, aren’t we?” I felt nothing. No hunger. The date had been enough for me. One.

“Yes. The remains of great kings. We will enter through this labyrinth, this blue light, I say, of eternity. Light cannot make you anticipate.”

An orange-to-gold hue first. Yes, the horizon reddened, as we moved. Before all was the vividness, all things drawn with an exacting shadow. A final issue of dark spread over great, redundant masks of architecture, each etching, yes, of fallow, deepening soil, the concept of a single burial mound, all of the building about now flooded with tints of this light, an elaboration of night sky. Traced with hollow gold. We passed under columns, a geometric cliff. “Deir el Bahri they will call it, those who come after. My people’s temple. Where you either dress, or undress. It doesn’t matter which. Where you prepare for knowledge.”

I knew what made of night a constant, insatiable burning for day. Calm, nascent, near. This was the cave of night. Pyramids stood below us, continents, triangles, space, as we descended.

There are no secrets. There are only those who say life is a lie. We were husband and wife. We were stepmother, and son. “Hatshepsut.”

Yes, I said it. Hatshepsut.

“You are not Anna, then. There is no Anna.” Anubis had large teeth. Anubis smiled. It was a wicked smile.

“You’ve brought me here.”

“I didn’t have to tell you this.” Little more than bearer, animal. I did hate this embalmer, exterminator. It was ruthless. “Thutmose, of the three names. Your stepson. It is he you have come for, whom you ruled with, fifteen years.”

I stared at the dog.

“After your death, yes, your stepson and then your husband, Thutmose, after his father’s death and then your own, defaced all your images. Your boy king did this, eradicated your dreams. All memory of you, the breviary of your face. All women are alike. The milk is taken.

This is the nature of daydream. We wake, among the lies. We dream, among the possibilities. Not that the mind lives alone, but that the seed, animate, leaves the bearer behind.”

I had to say it, Anubis, now, not more than a carver of rotten meat, a scavenger.“I would not let him rule alone.” I hadn’t moved an inch, from anywhere. “He was too young. I ruled as a woman would, in his place, I kept my face above his, even as I held him. Why should I share with a boy, for that matter, a man?”

I’d come from a bed, where you waste, where your scents evaporate. Why should I be appalled by a memory. I could have slept. Why would we be haunted?

“Life betrays all who live, don’t you know this?”

I left his words behind. I entered in, at the tip, rock spire. The last, deepest thought lay before. It was a room, as when you clear your mind of fault, everything familiar.

No, nothing had been touched. I came for my own thoughts.

“Thutmose seduced me, corrupted me. Then death, too, corrupted himself, his eyes, what he saw. It was finished, diminished to dust, piled articles, wheels for a chariot, a tiny boat, of gold, for sailing–and, laid among insects, the whittled likeness of a mongrel, would-be embalmer.”

I opened them, the lids. I’d thought him my child, I thought the revelation would show a man, at once cruel, aging, abstract, suspicious, yes, he had closed my eyes before he defaced me, scattered my effects, and had merely lingered after me with another queen. The bed, abandoned, belonged to an eighty year old. I could not keep it waiting, my watery glass, my most emerald pool. I would sleep with my dog on my mind.

You’re right, dead, now, myself, yes, you want to say–lost in death–he struck my images from the earth.

Yes, I’d come, now, from a bed–where you waste, where your scents evaporate. I tell you this. He did resemble a dog. A memory, any memory, raises you, unnecessarily. He’d brought me back. I could have slept. Why would we be haunted? Why? Is it thought? How can nothing leave us behind?

“Life betrays all who live, didn’t you know this?” Anubis grinned, salivated. “Is this place what we think it is, totally beautiful–or an enormous cemetery, corpses in dirt, lost prey?”

I took his hand, yes, I. We entered at the tip, I knew where, the rock spire. No one dragged me. I led. This last, deepest cave lay before. It was my necessity, as when you clear your mind. How often do you do this?

Our sleeves caught on nothing. We descended, yes, stumbled, everything disconcertingly familiar. Nothing, I say, had been touched. Time stopped.

Thutmose, this little man, had seduced me, corrupted me, and, as always, he, himself, in his own turn, had been corrupted, forsaken. This was history. No longer a sharpened knife edge. important. Death had met him, yes, stole his KA, his eyes, his everything.

Dust, piled articles, wheels for a chariot. Yes, a male. An ascendant male. A tiny boat, of gold.

Anubis, my mongrel, now himself also–among the insects, termites, we feel them, under our bed, now painted wood, a token of fear, statue, shall I say, paws, four of them, laid flat, over casket wicker.

I opened it, with my hands, this toy-like menace, I say I did, no one else, the many pretty lids of the enclosure. I’d thought of him, Thutmose, yes, my child, face, hands, the women who heaved him up also dead, only before, therefore, less than I. I was excited. The dust hovered, I thought it might reveal a man, cruel, aging, abstract, suspicious, what he had done to me.

I saw him close my eyes, he had done this, yes, because he had stood over me, briefly, in my moment of silence, in all that living had happened.

Call it a womb, a basket. Myself. Myself only. I saw, however, an infant, shake its fist. And understood, beyond loyalty, faceless love. His true mother would have heard his actual cry, as he had lingered after me, in this unattainable beauty.

Was it, after all, dissolution? You look at the street light, through window screen, you see the light of another, better life. It is there, in your head. The bed, after all, I’d left, abandoned, had belonged to an eighty year old. Someone, anyone, I hardly knew. She, I, Anna, Hatshepsut, watery glass, on the most perfect day. This is not, and must not be, effacement.

Craig Curtis has published widely over the last several years. His work has appeared In the New England Review, The Iowa Review, Confrontation, The Harvard Review, Chicago Review, and Carolina Quarterly, among others. He lives in Idaho.

Read More »

Claudia Owusu is a Ghanaian-American Writer and Filmmaker based in Columbus, Ohio. She writes from these two liminal spaces, internally and externally, trying to make sense of them. She believes in the beauty of community and the intimate stories we share when we think no one is listening. Her work often engages the spaces that Black women and girls occupy, namely their relationship with safety, being carefree, and self-ownership. Her writing has appeared in Vogue Magazine, Clockhouse,Quiz & Quill Literary Magazine,

Claudia Owusu is a Ghanaian-American Writer and Filmmaker based in Columbus, Ohio. She writes from these two liminal spaces, internally and externally, trying to make sense of them. She believes in the beauty of community and the intimate stories we share when we think no one is listening. Her work often engages the spaces that Black women and girls occupy, namely their relationship with safety, being carefree, and self-ownership. Her writing has appeared in Vogue Magazine, Clockhouse,Quiz & Quill Literary Magazine,