One spring Saturday in York County, Pennsylvania, my husband Fred picked up a five-gallon aluminum gas can he’d left on the asphalt by our garage over the winter. I was cleaning out the vegetable bed when I heard him call to me. Expecting to see some small wonder, of which our acre yields many, I dropped my rake and headed across the yard.

Flattened to the asphalt where the can had rested all winter lay a large, gummy-looking, desiccated toad, about the size of Fred’s palm. “How did it get under the can?” we wondered. It seemed impossible. After marveling with me for a while, Fred walked off to tinker with the tractor, leaving me to contemplate the grim expired thing, its corpse a shade of yellow-orange that I associated with the can’s gasoline. Though I saw no sign of a leak, I imagined the creature petrol-soaked, its bones dissolved, its muscles goo.

Perhaps to wash away the strange, sorry sight, to loosen the thing for removal, I fetched the garden hose and ran water over the flattened amphibian. Something happened, some shift, and I doubted my eyes. The animal was plumping, un-flattening, inflating with life as the water showered down.

The toad’s metamorphosis took only a few minutes. Not only did its splayed two-dimensional form morph into compact three-dimensionality; its color shifted from that sickly yellow-orange to speckled grey and brown, becoming recognizably Anaxyrus Americanus, the eastern American toad. Now animate, it hopped its way across the drive to the leafy debris beneath an old tulip tree. Amazed by what I witnessed, I followed it with the hose, dripping water on its back until it seemed to hunker against the flow, annoyed. It had had enough. Eventually I turned my attention back to the garden. Later, when I checked to see if the toad was still where I’d last seen it, it was gone.

The eastern American toad hibernates in winter, usually digging backwards to a depth below the frost line. This toad had hibernated under a gas can, it seems, well above the frost line during a winter that had seen a prolonged, hard freeze, and it had survived. It afforded me a rare sight—a toad’s emergence from hibernation, hastened by my showering garden hose.

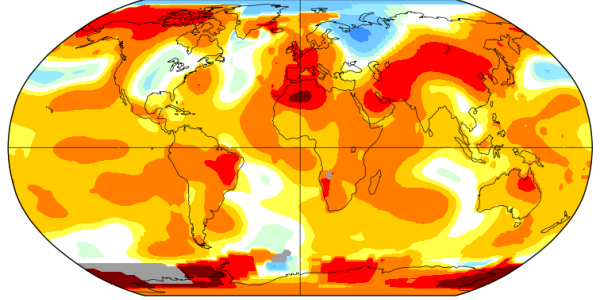

Although the toad seems to have been safe from gasoline contamination after all, I associate its revivification with the remarkable unpredictability and resiliency of life, even against the threats posed by that most lethal species nature has known, homo sapiens, with its oil spills, drift nets, radioactive waste, fracking chemicals and, as it turns out, five gallon gas cans.

About a quarter of a mile from our acre, we have a daily and mighty reminder of that lethal power: the ailing southern reaches of the Susquehanna River flowing toward the similarly ailing Chesapeake Bay. Along the trail above the river in springtime we see dark vernal pools dense with BB-sized frog eggs and, later, boiling with tadpoles. Across the River, on the Lancaster County side, we see afternoon light on the Chiques Rock outcropping, a kind of miniature Half Dome. Sometimes we see turtles sunning on the rounded rocks that rise above the powerful flow, sometimes bald eagles floating over the Route 30 bridge, or herons and ducks by the river’s edge, though fewer than before.

For all its life and beauty, the river always carries a weight of loss for us. Melancholy accompanies us on our river walks. Twenty years ago, my husband would reel in small-mouth bass all the day long, most released, a few pan-fried. He hasn’t caught one in more than fifteen years. Just stopped trying. His bass boat sits idle in the carport.

Multiple stressors, including pharmaceuticals and agricultural run-off, have decimated the Susquehanna’s bass population. If you catch a rare smallmouth these days, it’s likely to have open sores and sexual deformities. For years, the Executive Director of the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission, John Arway, has appealed to a succession of Governors and the state Department of Environmental Protection to designate the Susquehanna an impaired river. The designation comes with costs, of course. In 2015, the Pennsylvania DEP designated only the four southern-most miles of the river “impaired,” and those only with regard to PCB’s in catfish. They pointedly avoided and deferred action on the smallmouth bass problem. No will.

Last August we took visiting relatives up Chiques Rock for a magnificent view of the river. From high above, in the hot sun, we watched curtains of neon green algae sway in in the rocky shallows. Fed by agricultural nutrients, in some places algae choke the river. When I pointed them out to the new husband of a niece I hadn’t seen in years and mentioned the sad state of the river and the bass, I sensed what seemed like something stronger than indifference. He asked no questions, offered not so much as a “Hunh,” even turned a few degrees away from me. I stopped talking.

Fred reminds me in my hours of gloom: smallmouth bass were barely there a century ago; they swam into a new niche some time after the Susquehanna’s native trout died off from the warming and polluted waters left by the coal and logging industries of the previous century. An almost dead river rebounded. It became a new river, vibrant with new life. “It’ll happen again,” he tells me.

Indeed, rumor has it the Susquehanna smallmouth bass population has started to grow again. And crab numbers are rising in the Bay, though its oysters show no sign of recovery. The rise in bass and crab numbers owes much to two changes in agricultural practices in our region: the increased planting of cover crops for winter and the adoption of no-till farming, both of which stabilize the soil and reduce toxic run-off. Every farmer we know in our township, even the most conservative old-timer, has adopted no-till practices. “It just makes sense,” Jed tells me from behind the counter while I peruse the potatoes at Lehman’s farm stand. “You save a lot of water that way.” As bass numbers begin to creep up, some local anglers are pushing the state to lift a ban on bass fishing in the Susquehanna. Arway agrees that the numbers have risen slightly in the past few years but sounds a note of caution: the “young-of-the-year” smallmouth still show signs of disease; the river is still impaired, regardless of angler’s wishes or political will.

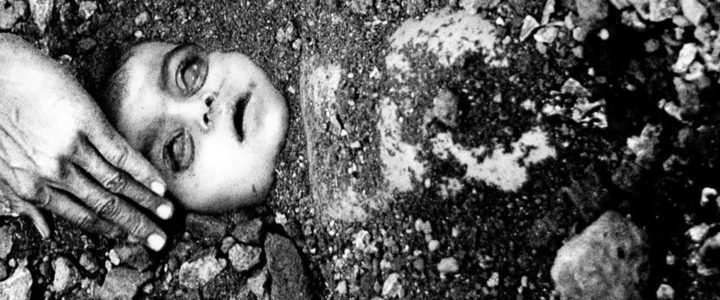

But the increase in numbers of bass makes clear what the geologic record shows again and again: given the chance, after devastation, life recovers. I cling to this fact. Finding solace in life’s regenerative capacity often requires taking the long view, however—longer than the timescales we naturally conceive and inhabit. Recovering biodiversity from the grave losses that characterize this age of ecocide will take more than a spring day or a season or even a lifetime to see. But this isn’t the first mass-extinction Earth has seen, I tell myself.

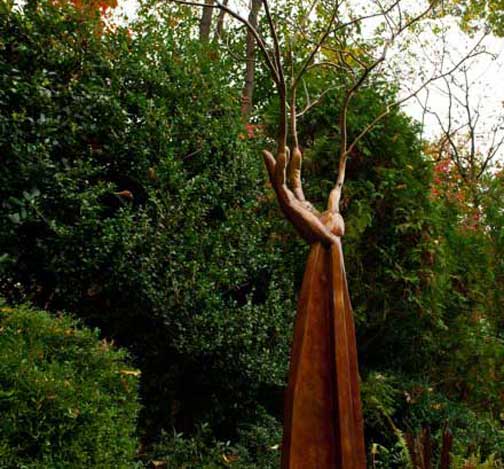

Since the election, with dispiriting news of swift action to weaken protections for air, water, species and places, future losses are sure to be even greater than what many of us had already expected with dread. It feels like someone lifted that can and, catching a glimpse of the toad, just slammed it back down again, maybe even piled on a few rocks for good measure, insisting with petulance, “Here I will rest my can!”

We must push those hands away, scatter those rocks, shower the revivifying waters to the extent that we are able. But the world will never “recover” exactly what was, what is. Trout will probably never repopulate the Susquehanna. Its smallmouth bass might finally go the same way. Just as their numbers start to rise, the new Board of Supervisors in our township has decided to repeal an ordinance requiring a buffer zone around rivers and streams, against many voices in protest. Old June Evans, erect, clear-eyed, formidable, came to every meeting with a binder full of facts. She stood and spoke. I watched and listened with something like awe. And when I spoke, I thought of June as much as anyone in that room. She seemed to know these lands for generations. Last week, she collapsed, a massive stroke: another face of nature’s unpredictability. I’m not the only one of this place who feels orphaned in her absence. I had hoped to know her better.

Still, the memory of that toad’s astonishing transformation, which turns out to be an ordinary thing for toads, soothes a bit my ongoing grief and worry. I imagine a warmish evening in early November when Fred put that five-gallon gas can down on the asphalt by the garage, not noticing an inconspicuous grey-brown creature resting there. Once the pressure lifts—if it lifts in time—life rebounds. Of course, things might have gone otherwise for that toad had Fred lifted the can who-knows-how-much later. Things go otherwise for countless creatures and systems the world over. Many an organism, pack, school, flock, herd, habitat, species will see no resurrection. In time, however—and probably much longer than I’d like—new life will emerge to crawl or slither or hop its way upon a new Earth.

Judith C. Mueller, teaches courses in literature and environmental studies at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster PA. Her essays have appeared in The Journal of Wild Culture and ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, among other venues. She lives and writes in an edible forest near the Susquehanna River.

Read More »

Ghana Imani (Hylton) is a writer & poet who honed her spoken word skills in the Brooklyn poetry scene and became a featured artist at the Brooklyn Tea Party, Nuyorican Poets Café, The Point, African Globe Studio Theater and other spoken word venues. She shared the stage with The Vibe Khameleons, RhaGoddess, Tantra, UNIVERSES, Mariposa and others. She has done voice-overs for national ads such as Sprite and Hot.97. Her most recent essay can be found in We Got Issues! A Young Woman’s Guide to A Bold, Courageous and Empowered Life. She was recently quoted in The Cover That Time Forgot in the Root.com online magazine. She’s volunteered at a number of non-profits over the years: She is a member of the MFEE (Montclair Fund for Educational Excellence) volunteer team. She led the #SayHerName Creative Writing & Poetry for Youth creative writing and poetry cipher in Newark NJ for young girls aged 12-17. Ghana uses her various skillsets to pursue passions in social justice, writing, education, women’s empowerment, and addressing the intersectionality of racism, sexism and other forms of oppression. She returned to her hometown of Montclair after living for 20 years in Brooklyn NY with her music teacher husband and their three children.

Ghana Imani (Hylton) is a writer & poet who honed her spoken word skills in the Brooklyn poetry scene and became a featured artist at the Brooklyn Tea Party, Nuyorican Poets Café, The Point, African Globe Studio Theater and other spoken word venues. She shared the stage with The Vibe Khameleons, RhaGoddess, Tantra, UNIVERSES, Mariposa and others. She has done voice-overs for national ads such as Sprite and Hot.97. Her most recent essay can be found in We Got Issues! A Young Woman’s Guide to A Bold, Courageous and Empowered Life. She was recently quoted in The Cover That Time Forgot in the Root.com online magazine. She’s volunteered at a number of non-profits over the years: She is a member of the MFEE (Montclair Fund for Educational Excellence) volunteer team. She led the #SayHerName Creative Writing & Poetry for Youth creative writing and poetry cipher in Newark NJ for young girls aged 12-17. Ghana uses her various skillsets to pursue passions in social justice, writing, education, women’s empowerment, and addressing the intersectionality of racism, sexism and other forms of oppression. She returned to her hometown of Montclair after living for 20 years in Brooklyn NY with her music teacher husband and their three children.

Michael Montlack is the author of the poetry book Cool Limbo (NYQ Books) and the editor of the Lambda Finalist essay anthology My Diva: 65 Gay Men on the Women Who Inspire Them (University of Wisconsin Press). Recently his poetry appeared in North American Review, Barrow Street, Hotel Amerika, Tupelo Quarterly, Poet Lore, The Cortland Review, and Painted Bride Quarterly. He lives in NYC.

Michael Montlack is the author of the poetry book Cool Limbo (NYQ Books) and the editor of the Lambda Finalist essay anthology My Diva: 65 Gay Men on the Women Who Inspire Them (University of Wisconsin Press). Recently his poetry appeared in North American Review, Barrow Street, Hotel Amerika, Tupelo Quarterly, Poet Lore, The Cortland Review, and Painted Bride Quarterly. He lives in NYC.

Marisol Baca is the author of Tremor, a full length collection of poems forthcoming from Three Mile Harbor Press. She was born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and grew up around generations of family in an old adobe house with a horno in the back that her father built. Her family later settled in Fresno, California. She grew up within a family of educators, artists, and writers, and at an early age began writing poems and songs. Marisol received her bachelors in English from Fresno State University and won the Andres Montoya poetry scholarship prize. She received a fellowship from Cornell University, and in 2006, she received her Master of Fine Arts. While at Cornell, she won the Robert Chasen poetry award for her poem, Revelato. Currently, Marisol is an English professor at Fresno City College. She lives in Fresno with her husband in a house in the center of town. She continues to write and teach, and is busy working on her second book. Her poetry has been published in Riverlit, Shadowed: An Anthology of Women Writers, Asentos Review, among others publications.

Marisol Baca is the author of Tremor, a full length collection of poems forthcoming from Three Mile Harbor Press. She was born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and grew up around generations of family in an old adobe house with a horno in the back that her father built. Her family later settled in Fresno, California. She grew up within a family of educators, artists, and writers, and at an early age began writing poems and songs. Marisol received her bachelors in English from Fresno State University and won the Andres Montoya poetry scholarship prize. She received a fellowship from Cornell University, and in 2006, she received her Master of Fine Arts. While at Cornell, she won the Robert Chasen poetry award for her poem, Revelato. Currently, Marisol is an English professor at Fresno City College. She lives in Fresno with her husband in a house in the center of town. She continues to write and teach, and is busy working on her second book. Her poetry has been published in Riverlit, Shadowed: An Anthology of Women Writers, Asentos Review, among others publications.

Chaya Bhuvaneswar is a practicing physician and writer whose work has appeared in Nimrod, Bangalore Review, Blue Lake Review and the Asian American Literary Review, and received a Henfield Transatlantic Writing Award as well as a Glimmer Train Honorable Mention and scholarship to Squaw Valley. She is at work on a novel and lives in the US with her family.

Chaya Bhuvaneswar is a practicing physician and writer whose work has appeared in Nimrod, Bangalore Review, Blue Lake Review and the Asian American Literary Review, and received a Henfield Transatlantic Writing Award as well as a Glimmer Train Honorable Mention and scholarship to Squaw Valley. She is at work on a novel and lives in the US with her family.

Paul Genega has published five chapbooks and five full-length collections of poetry. His sixth full-length collection, Sculling on the Lethe, will be launched by Salmon Poetry (Ireland) at the AWP Convention in Tampa, March, 2018. Over a forty-plus year career, his poetry has garnered numerous awards, including the “Discovery Award,” five Pushcart Prize nominations and an individual fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and his work has appeared in leading magazines and journals such as New York Quarterly, Poetry, the New York Times, The Nation, and The Paterson Literary Review. As a playwright, he has co-authored two works with Emmy Award winning composer/filmmaker Patricia Lee Stotter: Haven’t We Met?, which was presented at the Writers Theater in New York, and Paging Doctor Faustus, which is currently being readied for workshop production. In 2014, Genega assumed directorship of Three Mile Harbor Press upon the death of its founding editor Antje Katcher. He taught for many years at Bloomfield College, New Jersey where he founded the creative writing program and served as Chair of Humanities. His legacy continues at Bloomfield through the Genega Endowed Scholarships in Creative Writing.

Paul Genega has published five chapbooks and five full-length collections of poetry. His sixth full-length collection, Sculling on the Lethe, will be launched by Salmon Poetry (Ireland) at the AWP Convention in Tampa, March, 2018. Over a forty-plus year career, his poetry has garnered numerous awards, including the “Discovery Award,” five Pushcart Prize nominations and an individual fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and his work has appeared in leading magazines and journals such as New York Quarterly, Poetry, the New York Times, The Nation, and The Paterson Literary Review. As a playwright, he has co-authored two works with Emmy Award winning composer/filmmaker Patricia Lee Stotter: Haven’t We Met?, which was presented at the Writers Theater in New York, and Paging Doctor Faustus, which is currently being readied for workshop production. In 2014, Genega assumed directorship of Three Mile Harbor Press upon the death of its founding editor Antje Katcher. He taught for many years at Bloomfield College, New Jersey where he founded the creative writing program and served as Chair of Humanities. His legacy continues at Bloomfield through the Genega Endowed Scholarships in Creative Writing.