A broken clothesline leans

against its shadow

nothing to hang memories

on

through the stillness of

the desert landscape

I meander

fragrance of creosote bush

underfoot

dry winds blow

clockwise

shifting transverse

ridges of sand

In the distance a

prickly pear cactus

tempts the coyote

despite needles

the coyote

consumes

its fruit

spreading seeds

every thing

transient

even the

shadows

I stuff my backpack with the basic essentials, orient my body toward west and head out into the cooling desert. Barren hills unfold in abstract patterns against the fading orange and yellow light. During the past year I’ve learned much since leaving my suburban New York home. I’ve given up most of the possessions I’d amassed in my 55 years on the planet. I’ve evolved to adapt in my new environment. I no longer fear the desert. I trust the land and what it offers. I accept everything now and better understand its purpose. I’ve learned to let things go and see where they fall.

I squint my eyes into the last rays of the setting sun, until they pull back from view. The sagebrush smells sweet. Next to a prickly pear cactus a pile of stones mark the point where I enter the river bed and the path begins. Last month after two days of torrential rains, this serene spot turned into a violent river. Flash flooding occurred when the banks could not hold the volume of water. Dried creeks swelled to become raging rivers. A child playing in his backyard was swept away. They searched every inch of the land but could not find him. His parents own a condo at Moriah Heights. He was their only child.

As I approach my night time perch, a faint cluster of stars emerge in the darkening sky.

“Once the stars appear you’ll want to stay on that rock outcropping all night,” Mike said.

Mike was my boss and the person who hired me. A native to the area and head sales manager at Moriah Heights.

“Be careful out there as the river bed can be tricky at night. It can shift fast.”

“I’ll be fine.”

He leaned in close and put his hand on my shoulder.

“What kind of name is Eli?”

“It’s from the Bible,” I said.

“It’s got some kind of meaning?”

“Elevated one.”

He squeezed my shoulder with his fingers.

“Well listen, the desert plays tricks on us. No trees to orient direction. Make sure to take water in case you lose your way.”

“Will do.”

“And remember, I’ll need you at work at 6:30. Gotta get your rounds done before it gets too hot or it’s all lost. Don’t want you to dehydrate and pass out.”

Mike was tall with a tanned face and sharp features. He wore a cowboy hat with a huge turquoise stone attached by a braided string. He always had a pouch attached to his belt. Mike reminded me of one of those cowboys from the old rodeo posters. He was a half Navajo on his mother’s side. I couldn’t see it, but then again, how does one really know? His manner was stoic. At times he was elusive or maybe just stoned, I thought. But I learned to trust him. He mentored me in the ways of the land and reminded me why folks come out here to live.

“We got a lot of good paying residents here and their condos need to be attended to. They come here to enjoy the surroundings. Our job is to provide the best service to let them do that.”

My mind wandered, eddying on my thoughts of the grieving parents.

“You with me, Eli?”

“Yeah, I’m here.”

“Respond to their needs quickly and always with a smile.”

I had been thrown into all kinds of situations. From removing half-eaten poodles to clusters of bats occupying someone’s roof.

“Trap ‘em one by one with a cardboard box,” Mike said.

“But that might take weeks.”

“Look, if one’s rabid and you get bitten you’re a dead man walking.”

He knew everything about his surroundings but not much else I could tell. He was a survivor. I envied that. Once in a while I’d test him and ask about world news or the declining stock market. I wanted to know if he was tethered at all to the world outside the desert. He’d just move his head to the side and squint his eyes.

“It’ll change.”

Even when I told him something uplifting he’d reply the same way.

Along the sides of the path mariposa lilies bloom in spite of the harsh climate, because of it, really. Mike said that in the fall the flowers shed their seeds and germinate during the following winter rains. Several years will pass before a bulb reaches maturity and produces a flower.

“Because they’re buried deep in the earth, they can survive the wildfires. It takes advantage of the nutrient-rich soil and lack of competition from other plants so the bulbs produce greater numbers of flowers than in average years. Might not see it right away, but the fire makes them fight and thrive.”

“We should all have patience like the mariposa,” I said.

“If you’re ever lost and have no food, you unearth their bulbs and eat them. Raw is ok, but I suggest making a fire and roast ‘em.”

I climb to the top of the rock and set down my backpack. The landscape spills out before me as the sky darkens, a tumble of rocks throwing lengthening shadows. Tonight there is a new moon, so the night sky will be at its blackest. The best time of the month to view what’s out there. In the distance, yip-howls of a male and female coyote pierce the air of this deepening night sky.

“Without a canopy of trees their harmonies swirl in a chaotic mix of sound,” Mike said. “This confuses their predators to think they are surrounded by a pack of hundreds. It’s an auditory illusion known as the beau geste effect, caused by a variety of sounds produced by a male and female coyote and gets distorted as it passes through the barren land. Two coyotes’ voices can echo and sound like three times as many.”

During evening walks my thoughts were prone to wandering in non linear ways, bouncing and fracturing off the walls of my mind like coyote howls. Sometimes I wonder about other travelers like me passing through here. Had there been any like me, maybe trying to figure out their life? I was here for a purpose. Not everyone leaves everything they strived for in their lives to one day just up and go. Mike said we are all bound by some kind of fate. I wasn’t sure I agreed but listened to his rationale.

If I was to leave my past world behind and maybe find my son, I knew I had to listen closely to what he had to say, to anything that could help me. He understood this world I had come to live in. He understood the moon and cycles and the creatures that called this harsh land its home. He didn’t read books to get his knowledge. He walked the land and observed and gleaned things in this way, through living on the land.

Are we bound by fate?

Upon reaching the top of the outcropping I lay on my back and look up at the infinite sky. The stars pulsate as if they are signaling something, distinct now, where before they’d been faint. I cover my ears with the palms of my hands and watch for a sign.

During the first few weeks in the desert I received daily texts from friends back home.

“How was your awakening today?” they’d ask. “You find God?”

They predicted I wouldn’t last more than a year. It was a matter of time before I’d come running back to the land of milk and honey Of course, it was no land of milk and honey for me. Not anymore.

“How’s the autumn colors…on the one tree?”

They made fun of the odd names of the gated communities; Bethel Hills, Canaan Vista and of course, Moriah Heights.

“Watch out for the Red Sea, can’t it part at any moment?”

I landed a job pretty quickly.

“Dumb work for an MIT graduate,” they said.

Eventually I grew tired of the sarcasm and stopped responding. I had my job and a rent-free cottage. It was all I needed. With a master’s degree in Mechanical Engineering I was able to figure things out pretty quickly.

“You’re in charge of all the maintenance at our wonderful gated community,” Mike said. “The infrastructure at Moriah Heights is your responsibility.”

“Got it.”

“I’ll get the folks to buy in,” he said, extending his hand. “You keep it running.”

We shook on this.

After 25 years behind the computer screen and endless meetings with clients, menial tasks and manual labor suited me just fine. I needed to breathe for a minute.

“Every morning you’ll pick up the garbage in the communal areas and sweep away the encroaching sand. There’s always more, you’ll see.”

My new job allowed me the space I needed to think. I even bought myself an easel and tried my hand at painting.

Leaving behind what I had, or what I lacked, was not a hard decision. My wife and I were no longer speaking to each other. My job stressed me to the point I started drinking to self medicate. I hated myself and my world, and the only thing that kept me grounded was my son, Zach. Once he left, or disappeared, I had no reason to stay.

“He must be using drugs,” my wife said, staring into space. I knew she was in pain, too, but we couldn’t reach each other.

“I don’t think so, darling. We would have seen signs.”

“Maybe he met someone or was abducted by some white supremist group.”

These thoughts went on endlessly.

The beau geste effect. It applied.

Impossible to tell what was real noise and what had echoed, fragmented, magnified.

“You’re his father and you don’t give a shit.”

“Of course I do.”

“So do something. Call the police.”

I cared more about Zach than anything else in my life. That she couldn’t see this is what put me over the edge.

“How could an 18-year-old boy just get up and go like that, disappear?”

Our friends couldn’t comprehend it. They were educated people, rational people. We’d all moved to the city after college. Once cool and gritty was now a place they did not want for their children. I didn’t see it that way.

“The place has turned into a dangerous shithole. Not what it used to be.”

Most of our friends’ kids had gone to school with Zach, one of the most competitive private schools in the country.

“The Jettisons are sending Tommy there,” my wife said.

“He’ll be sheltered.”

“Yeah, sheltered among the right people.”

Everything was for Zach so arguing with her was futile. As our only child she had him always in her rearview mirror. He was destined to repeat her father’s success but as a neurosurgeon. He was just a few days away from beginning the dream of every Westchester parent. Our friends termed it the great trek. One studies to seek wealth. No time to waste, so at eighteen their children had set their goals. This was the idea even though we all knew it was us the goal stemmed from: Law school, the medical track, or an MBA in finance; nothing else mattered. They wanted their childrens’ paths to insure greater wealth than they had amassed. The American dream. I had remained silent. I had not thrown Zach a lifeline, the assurance that there were other paths.

The great trek.

“He’s destined to be a brain surgeon,” she said.

I looked up from an article I was reading about the rapid pace of advancement with DNA sampling.

“We don’t know.”

“I’m his mother,” she said “I know.”

A day before his departure for college the walls came tumbling down. His best friend’s parents put together a BBQ and swim party for his class. A going away party and possibly the last time they’d see each other until Thanksgiving or Christmas break. Some were going to Stanford and already had plans to stay with family for the holidays in Marin County. Their great trek would begin in Silicon Valley. The goal was to land an internship at a tech firm to get their foot in the door. We planned with Zach that he’d come home right after the party. He’d help us seal up the boxes and carry them out to our SUV.

“How about you pick up sushi on the way home?”

“Sounds like a plan, Dad.”

We loved our sushi dinners together on Friday nights. Just the three of us chatting about everything from the books we’re reading to the latest film we saw. There was plenty of conversation to go around as we shared our sushi and dunked our rolls into the soy sauce, winced from too much wasabi. We never wanted those evenings to end.

“It’ll be really hard when he goes to college,” my wife said one night as she laid in bed.

I put down my book and rolled over to comfort her. I was surprised to feel tears rolling down her cheek, pooling on her pillow.

“It’ll be okay,” I said, touching her shoulder, then holding her. “We’ll have more time together to do things.”

She rolled away, disconnected. My hand dropped.

“Can you turn off your light, please. I’m done.”

Done

As I wrapped and taped the last box and slid it to the side of the room for Zach, I heard my phone go off. A long thread of texts from Zach.

The last one: “I’m not in control of myself. My thoughts are not in sync with my body.”

I felt queasy. I didn’t know if I should call for help.

“Hey Zach, I’ll call you now.”

But there was no answer.

“Give me a call as soon as you get this message,” I texted.

I saw the three dots and felt a wash of relief that he was at least responding.

“I have this recurring dream,” he texted. “I’m on a ladder, painting a ceiling. Then a blinding light enters the room through a crack in the roof. I can’t see the whole picture. It’s like this great, bright light coming out of the sky.”

For some reason my thoughts jumped to our walks in the woods together when he was a small child, maybe 6- or 7-years-old. He had so many questions. I loved his questions and loved trying to find their answers, to phrase them just right.

“Where does color come from? Also, where does light come from? Do magnetic fields produce sparks? Why does the earth revolve a certain way around the sun?”

He never stopped. More and more of my days were spent researching answers and then phrasing them for my six-year-old to be able to grasp.

“Dad is it true there’s a person out there that does all this?”

He wanted essential truths and I could only hand him more mysteries.

“Is there like a switch?”

“You’ll figure it all out one day.”

“How d’you know, Dad?”

“I don’t know for a fact, but I have a feeling.”

What else could I say?

By the time he entered high school he started to care less about sports and hanging out with his friends. He would spend hours on the Internet searching for information about light, the sun, the interior of the Sistine Chapel. My wife thought it highly unusual for a teenage suburban kid to give up his social life for this.

“It’ll pass,” I assured her.

Although I didn’t think it would. It was in line with what I knew of my son, his hungry mind wanting more answers, then still more. .

I looked back down at my phone as a new text came in.

“I’ll text you tomorrow once I have this all figured out.”

I knew that text would never come. I knew it.

After Zach disappeared I had to make a decision. Either I hire an investigator to look for him, or I sit tight, and let this new change happen. I believed in my heart that something would shift and he would see something that might solve his internal dilemma. I chose to wait. I myself had conviction that all things come if given the right amount of space and patience. The wealthy ‘burbs of Westchester County didn’t afford him either. I had my own thoughts as to where he might end up or when that call would come.

“I know we could have done something to prevent this,” my wife said, stone-faced, seething. She was directing her anger at me. She always knew when my thoughts weren’t in line with her own, even when I said nothing to indicate this.

“We did the best we could,” I said, looking for confirmation for myself that letting him be was the best way.

After his disappearance, our lives began to unravel. I began to have stomach flare-ups that would last for days. When I came home from work she’d be sitting there with a gin and tonic in one hand and her cell phone in the other.

“Did you speak to him about this?”

She was actually closer to the truth than she knew, but we couldn’t discuss it. I knew she knew the answer, she was just trying to pull it from me.

“No dear. I just think we should give him time.”

“I hate you,” she said and refilled her glass with gin.

At work everyone knew what had happened and no one agreed with my decision. Some of them knew Zach, and thought I did the most unparental thing one could do.

“An animal would never do that.”

I shrugged it off. They were helicopter parents who didn’t trust themselves, so how could one expect them to trust their own children? I believe we haven’t fully evolved yet. The more we accept this, the greater our understanding of our needs and ability to survive. I knew Zach was in the process of processing this for himself.

“Survival is the only way,” I said. “Zach is figuring out something now for his future survival.”

We protected him like a seed in a greenhouse for too many years. No animal would do that to their offspring. If I didn’t let go now, let him follow this brave new path he’d forged, he would be stunted. At some point he would have no idea how to get through the turbulence of life. I feared he had no way to swallow the bitter pill.

This was the fundamental difference between my wife and me.

So on a sunny spring day, I poured myself a gin and tonic and sat down next to my wife.

“Looks like you’ll let the garden grow wild this year?”

“I handed my boss my resignation letter. I also met with our family attorney. We’ll be fine, or I should say you’ll be fine. You’ll get monthly checks and can stay in the house as long as you want. If you ever want to sell, he’ll be there to help you. You keep everything from the sale so there’s nothing to argue over.”

She turned her head in my direction and sipped her drink.

“I love Zach more than anything. That’s why I didn’t go after him. I want to hear his voice and walk with him again. I know it might be a while, but something in my gut tells me he’s alright and recalibrating. I’ll let you know when I see him. I’m sure he would have found what he was looking for. My hope is it will happen soon.”

I glanced over at her. The anger in her face hadn’t budged.

“You know it all, don’t you.”

I took a deep breath.

“One thing I am sure about, he is never coming back here.”

“Don’t forget to charge the Tesla, Eli. Don’t want you to get stuck in the middle of nowhere.”

And I left.

I had this weird feeling the further I drove west the closer I’d be to him. The sunsets became more vivid as the trees gave way to shrub brush, then open land, and eventually desert. I thought about the setting of the Old Testament stories. The characters were always wandering about in barren lands like these. Whether it was a verdant oasis or near wells, the writers were also on a search. Their great trek was full of rich stories with metaphors and allegories. Stories of real people grappling with the same questions we deal with today. One thing was for certain, my Tesla’s charge was low.

“Heard you resigned?” my friend from the lab texted. “You heading out to find him?”

“No.”

My colleagues are engineers and scientists. Their experiments yield concrete and tangible results. They understand logic. Terra firma. Beyond this, they wouldn’t dwell.

It took me a few months to acclimate to the desert. The light and heat was unbearable when the sun was high but at night the land cooled down, became chilly. I grew to love the yip-howl of the coyotes, their voices circling in disorienting, eerie echoes. It was a great sacrifice to be out here but it felt right. I had come to realize over the past few years that I needed to change. Zach was not the only one. Maybe he’d absorbed what I’d been feeling. I had to reset my compass and set my priorities right. If not I’d die a lonely death surrounded by people who thought they knew me. My own wife didn’t know me. This knowledge had frightened me. On that spring day when I backed out of the garage of my Westchester house, I knew it was the last time I’d ever see it. I’d start to focus on my day to day existence. I wanted to get in touch with myself and finally get to know myself, be true to my own ideas and questions. I wanted to know what it was that I feared and what I truly loved. There was also a chance I might never see Zach again. I thought about this in my walks in the beautiful sunsets. The hours of solitude. I was at peace with it as Ihoped I could circle in on the logic for all of this. I didn’t know what it was even as I believed in it.

I remembered peeking into his room before he left for his friend’s going away party.

“Zach?”

He appeared to be almost in a trance. He was on the Internet looking at photos of the Sistine Chapel.

“What d’you know about this,” he said.

He didn’t move his eyes from the computer screen. He returned to the Sistine Chapel over the years. His interest always came back.

“I’m a bit confused these days, Dad.”

“About what?”

“Do we have power over our own lives?”

I sat down on his bed.

“Like let’s say I want to go against everything that was planned out for me. Just go.”

“Just go?”

He turned his chair around and leaned in close to me.

“Do we have any control over ourselves?” he whispered. “Any power to move in our own direction? If we become subservient to fate will the human race end up in despair? What if we resist it all?”

I’d remembered this conversation when he sent that text, the last text before he left.

These days while on my evening desert meanders, I think about the same things. I didn’t want to fade away like dust and die a lonely man in a world of familiar people. Like him, I had to move on and continue to live, end if it meant giving up everything I had and starting from the beginning.

When I got home from my stargazing, I’d sit down on my computer until late into the night and check if there was any sign on Zach’s social media sites. His pages were still up, but he’d deleted his headshots.

One day Mike and I went out for beers. He advised me to stop thinking about my son, to unfollow him.

“You’ll lose yourself. He’s not where you’re looking for him anyway. He’s not on the screen, Eli.”

“How are you so sure?”

He bought me a beer and told me the story of his Navajo grandfather.

“He carried a little pouch with him whenever he went out. Told me it was to collect memories ‘cause they don’t last. We forget and they fade.”

“He plucked at leaves from the chaparral and steeped it for tea. It tasted like shit but out of respect we drank it.”

“You’ll remember that,” his grandfather had said.

“And he was right, we sure did.”

He went on to tell me about his wife’s battle with cancer. She was his high school sweetheart. They got married when they were both twenty-one and she was diagnosed with a rare cancer a few years later.

“After she passed I was devastated. I was like this walking zombie. My grandfather said to forget her. Put her out of your memory.”

“That’s tough.”

“She was the only girl I ever had so it was hard, but my grandfather had this wisdom of years. We all respected him so I figured it was worth trying.”

“When you can no longer remember what she looked like, you’ll receive a sign,” his grandfather said. “Then you can search for her spirit, be one with her again.”

Mike leaned forward. I could feel his breath.

“Some said he was crazy but I believed in him. There’s lots of magic around here.”

I was beginning to understand.

“Get off of his Facebook page,” Mike said. “Stop searching.”

He signaled to the bartender for the check.

“Supposed to be a great sunset tonight,” he said. “Let’s take a look.”

He put his arm around me and sang a few verses of an old Eagles song. I sang with him.

“Strange concept,” I said.

“The sunset?”

I waited before answering him.

“To forget everything.”

During the next few days I tried everything to block out memories. If my thoughts wandered back to Westchester, or to Zach, I’d shut my eyes and remember the lyrics to the Eagles song. I kept busy with my handyman work. It helped to get my mind off Zach and everything in my past. One day I got a call from my attorney in New York about our investments. My wife needed more money for new medications. Our insurance wasn’t covering them, so I made some calls. I laid down on my couch and thought about the mess I left back home.

“When you start to drift back, go out and find the creosote bush,” Mike said. “Rub the leaves and inhale. It extracts moisture from parched soil through its root system so the leaves smell like rain. They’re hearty bastards and can withstand high temperatures and dehydration. Put some leaves in your pouch. They cure all kinds of ailments. My grandfather called the bush the anointed one.”

After a few weeks I actually started to forget. I had my work during the morning and afternoon, the sunsets in the evening and out stargazing at night. Folks in the complex started warming to me. I stayed off social media like Mike said and only used the Internet to learn more about the desert. I even started to read the Old Testament as Mike hounded me every day about my name and more meanings. I told him about the namesake of the complex where we lived. He was intrigued about the story of Abraham and his son.

“I could never kill my son.”

“It’s just a metaphor,” I said. “He was being tested.”

“Some metaphor. Tested for what?”

One day after work I was sitting on my deck with my binoculars. I spotted a coyote in the distance tearing at a cactus fruit. I was distracted by the sound of the voice message ring on my phone. The number was unfamiliar to me.

“Dad. It’s me.”

It was hard at first to be sure about his voice. There was so much crackling static and distortion in the background. I pressed the phone closer to my ear.

In the distance I could see dark clouds rolling in fast atop the high range in front of the complex. The highest mountain was called Mt. Moriah.

“I’m experiencing the most intense lightning storm I’ve ever seen. I’ve never seen anything like this. It’s beautiful.”

Then a thunderous crash and silence. I quickly called back the number, but no answer. I kept calling.

“Eli,” Mike said, screaming, in a state of panic. “The transformer was hit. There’s a fire near the maintenance garage.”

The storm was moving toward us, blackening the sky. Bolts of lightning flashed across the barren landscape. I could see a small brush fire where the coyote had been eating.

“Bring your tools and the extinguisher. Quick.”

I ran to the shed as my cell phone rang again.

“Hello, Zach is that you?”

There was a loud boom and then his voice.

“Dad, is that you…I am in the desert, dad. The sunsets here are so beautiful. Love you Dad.”

Then a loud bang and the call dropped again. Before I could process what had happened, another call came in. It was Mike.

“Our Welcome to Moriah Heights sign is on fire. I called the fire department but they told me it’ll be a while. I’m heading over there now. Come quick, Eli.”

When I arrived, the fire had consumed the giant wood sign.

“It took me months to make that baby. Carved it all by hand.”

The lights in the complex were flickering on and off.

“I worked so hard on that.”

As I walked toward the smoldering flames with my extinguisher he grabbed my arm.

“Let it go.”

“We can still salvage some parts of it.”

I noticed his eyes had welled up as he looked up at the dark clouds.

“Forget it. The rain is coming.”

He stared at the burning hunk of wood as it crackled then fell to the ground.

“You okay?” he asked.

“I am.”

“Good. I’ll call the residents. I’ll tell them they’ll be without power for a while.”

The rain smelled sweet as it moved closer and blanketed the dry landscape.

“Tomorrow there’ll be flowers,” Mike said, staring at the flames.

My mind held the memory of those mariposa lilies, vibrant yellows and purples echoing the sky above them.

“I’ll go and check the transformer.”

He grabbed my arm again.

“You hear from your son?”

I turned to look at his face.

“Yes, I think I did.”

“I knew you would.”

A lump entered my throat as the rain began to fall in a more steady rhythm.

“You hear from your wife?” I said.

He turned away from the fire and looked directly at me.

“There’ll be a flash flood in the morning. The dry riverbed will overflow. The parents that are grieving over their son will relive the horrible tragedy all over again.”

The rain was coming down in buckets. It fell over the sign and extinguished the embers from the smoldering wood. It sizzled, then fell silent.

“He’s okay?”

“Yes, I think he is.”

“Tomorrow, if the roads aren’t washed away, I’ll buy wood for our new sign. While I’m gone you can remove the burnt stones and clear the foundation.”

“Sounds good.”

“Wait here. I want to give you something.”

He walked over to his truck and returned with a leather pouch.

“Take this to the grieving parents.”

I opened the pouch and inhaled the aroma. The fragrance triggered a flood of memories.

“Make them tea and sit with them.”As I turned away and walked back into Moriah Heights I heard the call and response of a male and female coyote. It sounded very close to where Mike stood. I turned and looked at his imposing figure.

“The anointed one,” I heard him call at me in between the yip-howls. “It’s a metaphor.”

Paul Rabinowitz is an author, screenwriter, photographer and founder of ARTS By The People. He is the author of 5 books including Confluence; The Clay Urn; truth, love and the lines in between; Limited Light and Grand Street, Revisited. Rabinowitz co-writes screenplays with Brittney Bertier including the TV pilot called Bungalow. Rabinowitz’s photography, prose and poetry appear in magazines and journals including The Sun Magazine, New World Writing, Arcturus-Chicago Review Of Books, Evening Street Press, The Montreal Review, Wilderness House Literary Review, Talking River Review, The Oddville Press and elsewhere. Rabinowitz was a featured artist in Nailed Magazine in 2020, Mud Season Review in 2022 and Apricity Press in 2023. His photo series Limited Light was nominated for Best of the Net in 2021. Rabinowitz’s poems and fiction are the inspiration for 8 award winning experimental films, including Best Experimental Short at Cannes, Venice Independent Film Festival, Oregon Short Film Festival, Jersey Shore Film Festival, Florence Indie Film Festival and Paris Film Festival. Rabinowitz has produced mixed media performances and poetry films that have appeared on stages and in theaters in New York City, New Jersey, Tel Aviv and Paris.

Paul Rabinowitz is an author, screenwriter, photographer and founder of ARTS By The People. He is the author of 5 books including Confluence; The Clay Urn; truth, love and the lines in between; Limited Light and Grand Street, Revisited. Rabinowitz co-writes screenplays with Brittney Bertier including the TV pilot called Bungalow. Rabinowitz’s photography, prose and poetry appear in magazines and journals including The Sun Magazine, New World Writing, Arcturus-Chicago Review Of Books, Evening Street Press, The Montreal Review, Wilderness House Literary Review, Talking River Review, The Oddville Press and elsewhere. Rabinowitz was a featured artist in Nailed Magazine in 2020, Mud Season Review in 2022 and Apricity Press in 2023. His photo series Limited Light was nominated for Best of the Net in 2021. Rabinowitz’s poems and fiction are the inspiration for 8 award winning experimental films, including Best Experimental Short at Cannes, Venice Independent Film Festival, Oregon Short Film Festival, Jersey Shore Film Festival, Florence Indie Film Festival and Paris Film Festival. Rabinowitz has produced mixed media performances and poetry films that have appeared on stages and in theaters in New York City, New Jersey, Tel Aviv and Paris.

Read More »

Marc Egnal is a retired professor, living in Toronto, and author of several books on US and Canadian history. His stories have been published in Freedom Fiction Journal and Lowestoft Chronicle. When not writing, he can be found walking my French bulldog, Holden, or playing with grandchildren.

Marc Egnal is a retired professor, living in Toronto, and author of several books on US and Canadian history. His stories have been published in Freedom Fiction Journal and Lowestoft Chronicle. When not writing, he can be found walking my French bulldog, Holden, or playing with grandchildren.

Paul Genega’s seventh full-length collection, Outtakes: New and Selected Poems 1975-2023, was published by Salmon Poetry in December, 2023. Over a long career, his poems have appeared in scores of magazines and journals, including Poetry, New York Quarterly, The Nation and North American Review. He is Professor Emeritus at Bloomfield College of Montclair State University in New Jersey where he founded the creative writing program, taught literature and writing, chaired the Humanities Division, and served as Chair of Faculty. Visit him at www.paulgenega.com.

Paul Genega’s seventh full-length collection, Outtakes: New and Selected Poems 1975-2023, was published by Salmon Poetry in December, 2023. Over a long career, his poems have appeared in scores of magazines and journals, including Poetry, New York Quarterly, The Nation and North American Review. He is Professor Emeritus at Bloomfield College of Montclair State University in New Jersey where he founded the creative writing program, taught literature and writing, chaired the Humanities Division, and served as Chair of Faculty. Visit him at www.paulgenega.com.

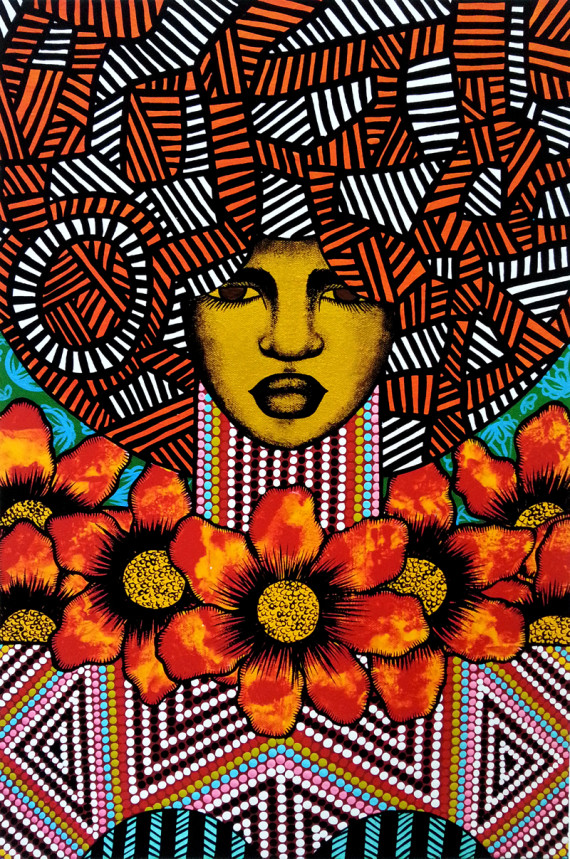

Megha Sood is an award-winning Asian-American author, poet, editor, and literary activist from New Jersey. Literary Partner with “Life in Quarantine”, at Stanford University. Her four poetry collections include the award-winning (My Body Lives Like a Threat, FlowerSong Press, 2022), (My Body is Not an Apology, FinishingLine Press, 2021), and ( Language of the Wound is Love, FlowerSong Press, 2025). She has received support from VONA, Pen Women, Dodge Foundation, Kundiman, and Martha’s Vineyard Writing Institute. Her 900+ works have been featured in print, online journals, public exhibits, and anthologies including the Poetry Society of New York, MS Magazine, NYPL, Pen Magazine by American Pen Women, PBS American Portrait, NPR, WNYC Studio, etc, and numerous universities including Stanford University, Howard University, George Mason, Columbia. Her poems and anthology The Medusa Project have been selected to be sent to the moon in 2025 as part of the historical LunarCodex Project in collaboration with NASA/SpaceX. Find her at https://linktr.ee/meghasood

Megha Sood is an award-winning Asian-American author, poet, editor, and literary activist from New Jersey. Literary Partner with “Life in Quarantine”, at Stanford University. Her four poetry collections include the award-winning (My Body Lives Like a Threat, FlowerSong Press, 2022), (My Body is Not an Apology, FinishingLine Press, 2021), and ( Language of the Wound is Love, FlowerSong Press, 2025). She has received support from VONA, Pen Women, Dodge Foundation, Kundiman, and Martha’s Vineyard Writing Institute. Her 900+ works have been featured in print, online journals, public exhibits, and anthologies including the Poetry Society of New York, MS Magazine, NYPL, Pen Magazine by American Pen Women, PBS American Portrait, NPR, WNYC Studio, etc, and numerous universities including Stanford University, Howard University, George Mason, Columbia. Her poems and anthology The Medusa Project have been selected to be sent to the moon in 2025 as part of the historical LunarCodex Project in collaboration with NASA/SpaceX. Find her at https://linktr.ee/meghasood

Paul Rabinowitz is an author, screenwriter, photographer and founder of ARTS By The People. He is the author of 5 books including Confluence; The Clay Urn; truth, love and the lines in between; Limited Light and Grand Street, Revisited. Rabinowitz co-writes screenplays with Brittney Bertier including the TV pilot called Bungalow. Rabinowitz’s photography, prose and poetry appear in magazines and journals including The Sun Magazine, New World Writing, Arcturus-Chicago Review Of Books, Evening Street Press, The Montreal Review, Wilderness House Literary Review, Talking River Review, The Oddville Press and elsewhere. Rabinowitz was a featured artist in Nailed Magazine in 2020, Mud Season Review in 2022 and Apricity Press in 2023. His photo series Limited Light was nominated for Best of the Net in 2021. Rabinowitz’s poems and fiction are the inspiration for 8 award winning experimental films, including Best Experimental Short at Cannes, Venice Independent Film Festival, Oregon Short Film Festival, Jersey Shore Film Festival, Florence Indie Film Festival and Paris Film Festival. Rabinowitz has produced mixed media performances and poetry films that have appeared on stages and in theaters in New York City, New Jersey, Tel Aviv and Paris.

Paul Rabinowitz is an author, screenwriter, photographer and founder of ARTS By The People. He is the author of 5 books including Confluence; The Clay Urn; truth, love and the lines in between; Limited Light and Grand Street, Revisited. Rabinowitz co-writes screenplays with Brittney Bertier including the TV pilot called Bungalow. Rabinowitz’s photography, prose and poetry appear in magazines and journals including The Sun Magazine, New World Writing, Arcturus-Chicago Review Of Books, Evening Street Press, The Montreal Review, Wilderness House Literary Review, Talking River Review, The Oddville Press and elsewhere. Rabinowitz was a featured artist in Nailed Magazine in 2020, Mud Season Review in 2022 and Apricity Press in 2023. His photo series Limited Light was nominated for Best of the Net in 2021. Rabinowitz’s poems and fiction are the inspiration for 8 award winning experimental films, including Best Experimental Short at Cannes, Venice Independent Film Festival, Oregon Short Film Festival, Jersey Shore Film Festival, Florence Indie Film Festival and Paris Film Festival. Rabinowitz has produced mixed media performances and poetry films that have appeared on stages and in theaters in New York City, New Jersey, Tel Aviv and Paris.